The Great Coven

By: Ana Teresa Benjamín

Illustrations: Martanoemí Noriega

Today, if we were to read the book written six centuries ago by Dominican monks Heinrich Kramer and Jacobus Sprenger to explain witchcraft and describe those most likely to practice it, it might appear humorous, if not for the fact that it contains many of the adjectives still used to describe women, or at least a certain type of woman.

The Malleus Maleficarum was commissioned in the 15th century by Pope Innocent VIII, who at the time feared that “all the heretical depravity” invading northern Germany and territories such as Mainz, Cologne, Trier, Salzburg, and Bremen prevented the flourishing and growth of the Catholic faith. By “depravity,” he meant the practice of witchcraft, which was blamed for “horrendous offenses, terrible pain, and pitiful diseases” such as the death of herd animals, the failure of crops, and infant mortality.

One of the sections of the book wonders why “women, above all, are addicted to evil superstitions” and answers the question with a string of imagined truths that continue to survive today: women are witches because they are malignant by nature, intellectually childish, have weak memories, and are impulsive and carnally insatiable.

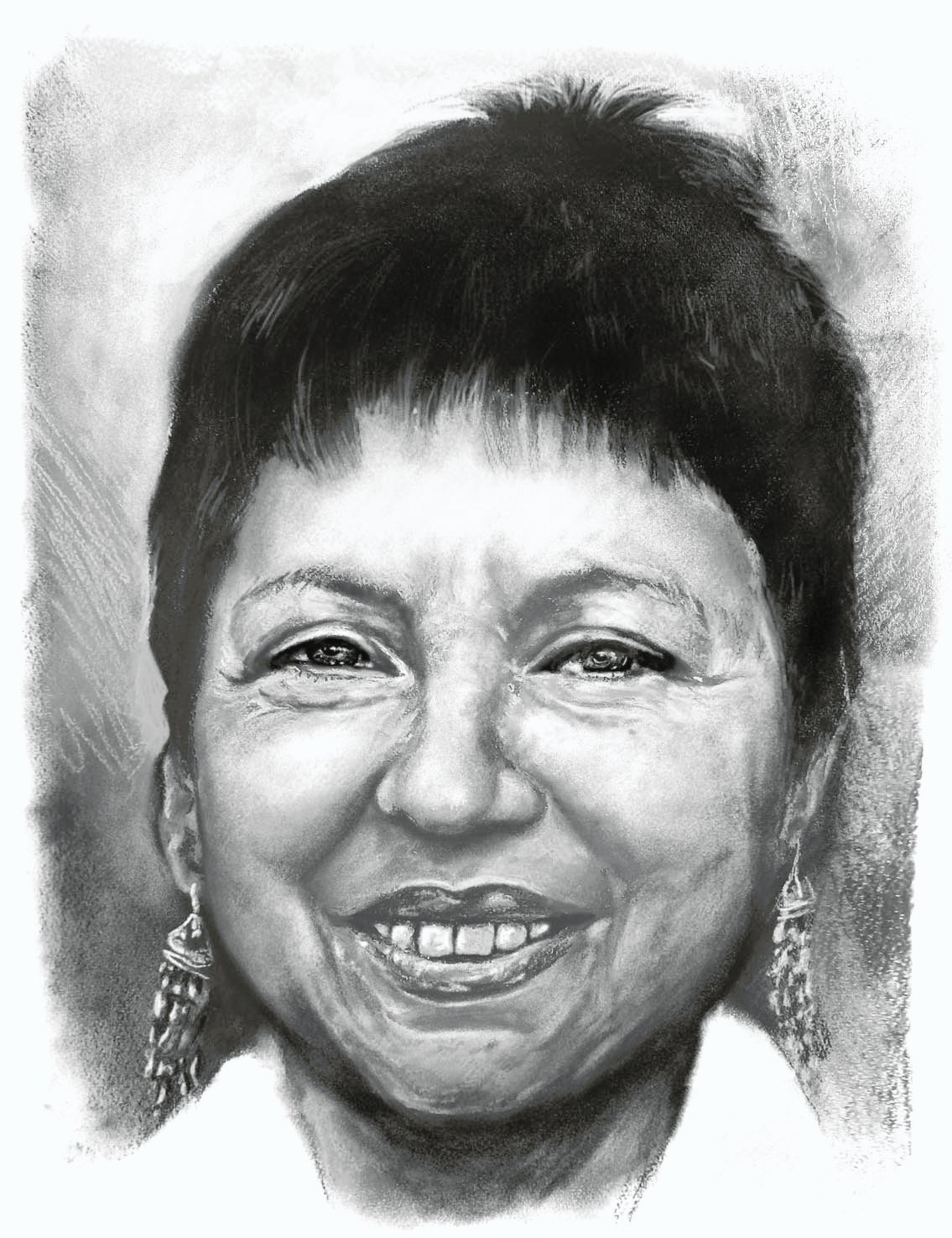

Angela Davis

Davis was born in the southern United States when Jim Crow segregationist policies were still in place. She lived in a place that was nicknamed “Dynamite Hill” because the Ku Klux Klan regularly bombed African-American houses there. As a child, she learned that hatred against black people was not a “natural state,” which perhaps explains her early ties to the Black Power and Black Panther movements. Her best known book is Women, Race and Class (1981), an analysis of anti-slavery struggles and women’s suffrage that centered on the need to reflect on the relationship between race, gender, and class.

They were “disgusting” not only because they surrendered to the “heresy of witchcraft,” but also because they dragged men –unable to resist their siren songs– down with them. “All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which is in women insatiable, turning men into animals through their magical arts,” Kramer and Sprenger wrote.

Amazingly, the Malleus Maleficarum became an instruction manual used by the Inquisition to establish punishments and justify the hunting, torture, and murder of women. Today it is clear that such accusations were ridiculous, of course, but they served as a form of social control and a political tactic during a historical period when the Catholic Church struggled to contain the Protestant religion and territories were in dispute.

And so, women were victims of those in power. As Panamanian feminist Alibel Pizarro says, we now know that those persecuted [for witchcraft] were healers and midwives, women who attended pregnancies and newborns and medicated with herbs. Mexican anthropologist Marcela Lagarde writes in Los cautiverios de las mujeres (Women’s Captivities) (1990): “The concept of the witch as someone evil arises in groups that do not recognize the positive wisdom in the experiences of the shamans and women,” and the Catholic Church was one of these groups. “In the Catholic mentality, the genesis of feminine power is evil. The witch is an ally of the devil; she obeys him. This image is in conflict with the ideal of faithful, submissive, obedient women.”

Gloria Anzaldúa

This Chicana born in Texas defines herself as a foreigner caught between the American and Mexican cultures. She is also a lesbian and this hybrid identity may explain her overriding interest in the diaspora, territory, and the eternal question: Who am I? Anzaldúa sees herself as at a “crossroads,” a borderland person. Her book Borderlands / La Frontera (1987) takes a look at the relationships between gender, body, race, and geographic border areas and how this “non-identity” ends up becoming a tool for social transformation.

Although during much of Western history women were relegated to secondary and subordinate roles, it is worth pointing out that during the period of the Inquisition, the term witch took on special significance. Over time, the adjective was used not only to group together women considered “evil, insatiable, and intellectually weak” but also those seen as inquisitive, nonconforming, independent, outgoing, and above all, disobedient. They were indomitable spirits who refused to be tamed.

At the end of the 19th century, women in certain European nations obtained the right to vote. Although suffrage was not universal, it was progress. When World War I broke out (1914-1918), women supported their families and countries while men went to the front. The same was true during World War II (1939-1945). In 1949, Simone de Beauvoir published The Second Sex in France. As Máriam Martínez-Bascuñán wrote in an article published on July 6, 2019 in the Spanish daily El País, men returned home and Beauvoir placed the woman’s body at the center of the debate: “If every human life is defined by its situation, a woman’s corporality and the social significance attributed to it condition her existence.”

Fourteen years later, American feminist and writer Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique (1963), questioning what magazines, newspapers, books, and advertising defined as the “essentially feminine.” At the time, images of the perfect housewife abounded; she was dedicated to her husband, children, and home, and had no ambition other than to make others happy, as Lagarde explained in her text captivities.

Simone de Beauvoir

Born in Paris, de Beauvoir was a teacher for a while, but eventually abandoned the profession to devote herself entirely to writing. Always very attentive to her surroundings, she supported the 1968 student demonstrations, condemned the invasion of Czechoslovakia, declared herself in favor of abortion, and took a keen interest in the Arab-Israeli conflict and the Chilean dictatorship. She wrote many essays, articles, and books, but the best known is The Second Sex (1949), which states that women are “made,” the products of imposed social norms. “[Woman] is determined and differentiated with reference to man and not he with reference to her; she is incidental, the inessential as opposed to the essential. He is the Subject, he is the Absolute –she is the Other.”

Friedan sought to destroy this false image of womanhood that was based on surrender, renunciation, and conforming to certain roles. She put into words this “problem that has no name” but she also posed a bigger question: Is that all there is? Is that all I can expect from life?

Women in the mid-20th century ― descended from survivors of the Inquisition, heirs of suffragists, and responsible for the continuation of society while their husbands went off to war― continued to be relegated to domestic roles as procreators and caregivers.

Shortly after Friedan, another American, Kate Millet, put forth the idea of sexuality as a political issue, which continues to resonate given the current discussions around a woman’s right to make decisions about her own body and the vehement ways many frame this as sinful and unnatural.

Oyèrónke Oyêwùmí

Nigerian by birth, Oyêwùmí criticizes Western academics, whose unilateral and universalist vision prevents them from understanding different cultures. In African Women and Feminism: Reflecting on the Politics of Sisterhood (2003), for example, she analyzes the oppression common among women and also questions the Western feminist perspective used to analyze African women. In The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses (2017, in Spanish), she states that the concept of gender in Yorùbá culture was implanted by the English and that the concept of “woman” is a product of colonialism. From here she goes on to question the prevailing idea of “biology as destiny” and establishes that social organizations do not require gendered bodies.

Women, in a way, are still seen as the witches described in the Malleus Maleficarum. Despite the many battles won, they remain at a disadvantage. Stepmothers and mothers-in-law, like women who stand up for their rights, fight for their freedom, or remain outside the norms of “femininity,” continue to be seen as witches. The same is true of women who denounce femicide and sexual harassment, female environmental activists, grassroots leaders, and those who call themselves feminists. In the words of Pizarro, “we feminists like to say we are the granddaughters of the women who couldn’t be burned at the stake.”

Among the countless “granddaughters” are many ordinary women, but also others, too many to be included here, who have made names for themselves: Egyptian Nawal el Saadawi, who once said that there can be no economic relationship in a romantic relationship because it inevitably leads to submission and submission ends in prostitution; Argentina’s María Lugones, recognized for her work on post-colonial feminism; Italian-American Silvia Federici, who affirms that the unpaid reproductive work and childcare performed by women are what sustains capitalism; Indian-born Chandra Mohanty, a defender of anti-capitalist feminism; Judith Butler, Wangari Maathai, Nancy Fraser… All feminists and revolutionaries and the kind of “witches” who used to burn at the stake.

Rita Segato

This Argentine anthropologist resides in Brazil, where she specializes in violence against women and the relationship between this violence and notions of power taught by patriarchal societies. Segato states that not only women, but men as well, are victims of patriarchy because men are constantly forced to demonstrate the manhood that is expected of them. She came to this conclusion after conducting an investigation with prisoners convicted of rape in Brazilian prisons. “Attributing crimes against women to mental health, hatred, or emotion limits the conversation. Gender crimes are political,” she claims, in the sense that the patriarchal political system supports and fosters this violence, and that the “mandate of masculinity” pushes the subject to demonstrate that he can control and invade the bodies of others. Among her most important books are Las estructuras elementales de la violencia (Elemental Structures of Violence) (2003) and La guerra contra las mujeres (The War Against Women) (2016).