México City’s National Museum of Anthropology

By Wilmer Góngora

Photos: William Bello

The museum, dedicated to preserving México’s indigenous heritage, welcomes visitors in an immense lobby that leads into a large central courtyard surrounded by eleven rooms devoted to archeology on the first floor and eleven rooms focused on ethnography on the second floor. The entry into this open-air space is crowned by the Umbrella, which opens up onto the Pond and the Mexica Room, occupying a deservedly privileged location as the custodian of the most precious jewel of all: the Sunstone. The overwhelming importance of this majestic enclosure makes it a must-see for Latin Americans who want to understand and honor their true roots. Here is a small sampling of just a few of the pieces on display.

The Umbrella

This monumental sculpture, which includes a waterfall, is covered by a bronze high relief piece titled Imagen de México (Image of México); it stands ninety-four feet tall, weighs 2,000 tons, and symbolizes the union of two cultures. The capital represents the sky. On the eastern side is an eagle, México’s national emblem; the faces of a native Mexican and a Spaniard; a ceiba tree, sacred to the Mayas; a sword; the rising sun; and the Eagle and Jaguar Warriors. The western side depicts the dove of peace, a man with outstretched arms, the nuclear symbol, the compass rose, and the sun.

The Sunstone

This monolithic disk carved from basalt is eleven feet in diameter, four feet thick, and weighs twenty-four tons. It records the movements of the stars and certain astronomical cycles with twenty-day months, eighteen-month years, and fifty-two-year centuries. The stone dates from the Mesoamerican Postclassic period, from 1250 CE to 1521 CE. The Spaniards buried the stone in order to “eradicate the memory of the ancient sacrifices performed there.” In 1790, it was rediscovered and mounted on an exterior wall of the Metropolitan Cathedral.

This monolithic disk carved from basalt is eleven feet in diameter, four feet thick, and weighs twenty-four tons. It records the movements of the stars and certain astronomical cycles with twenty-day months, eighteen-month years, and fifty-two-year centuries. The stone dates from the Mesoamerican Postclassic period, from 1250 CE to 1521 CE. The Spaniards buried the stone in order to “eradicate the memory of the ancient sacrifices performed there.” In 1790, it was rediscovered and mounted on an exterior wall of the Metropolitan Cathedral.

Mexica Room

This room occupies the central part of the museum and houses its most important collection of Aztec culture. The collection highlights the social, economic, religious, artistic, and political development of the Aztecs, or Mexica people, who founded the lakeside capital of Tenochtitlan in 1325. Aztec culture collapsed on August 13, 1521 when the Spanish conquerors razed the entire city.

Aztec Skull

Researchers have yet to discover why Aztecs and Olmecs covered skulls with crystals and other materials.

Ocelot or Jaguar

The powerful animal of the night, Tezcatlipoca, patron symbol of masculinity, graces the entrance to the Mexica Room in the form of a cuauhxicalli, the Mexica container used to deposit offerings. The depression on the animal’s back held the blood and hearts of captive warriors: the terrible food and vital force of the Sun.

The powerful animal of the night, Tezcatlipoca, patron symbol of masculinity, graces the entrance to the Mexica Room in the form of a cuauhxicalli, the Mexica container used to deposit offerings. The depression on the animal’s back held the blood and hearts of captive warriors: the terrible food and vital force of the Sun.

Coatlicue

The mother of the god Huitzilopochtli was worshiped as the mother of all gods in the late Postclassic period (1250 CE-1521 CE). She is depicted as a woman in a skirt made from snakes, with sagging breasts (symbolizing fertility), and a necklace of human hands and hearts torn from victims of sacrifices. The statue was found in 1790, during the remodeling of the Plaza Mayor in what was then New Spain.

Tlatelolco Market

This model of Tlatelolco Market, a lesser capital of the Mexica people, was built under the direction of Carmen de Antúnez in the 1960s. At the time depicted in the model, direct bartering was common: one product for another. In other cases, cocoa, powdered gold, copper hatchets, and textiles served as currency in exchange for valuables. The model is thirty-two feet long, eleven feet deep, and contains 305 human figures stationed around forty-four market spots.

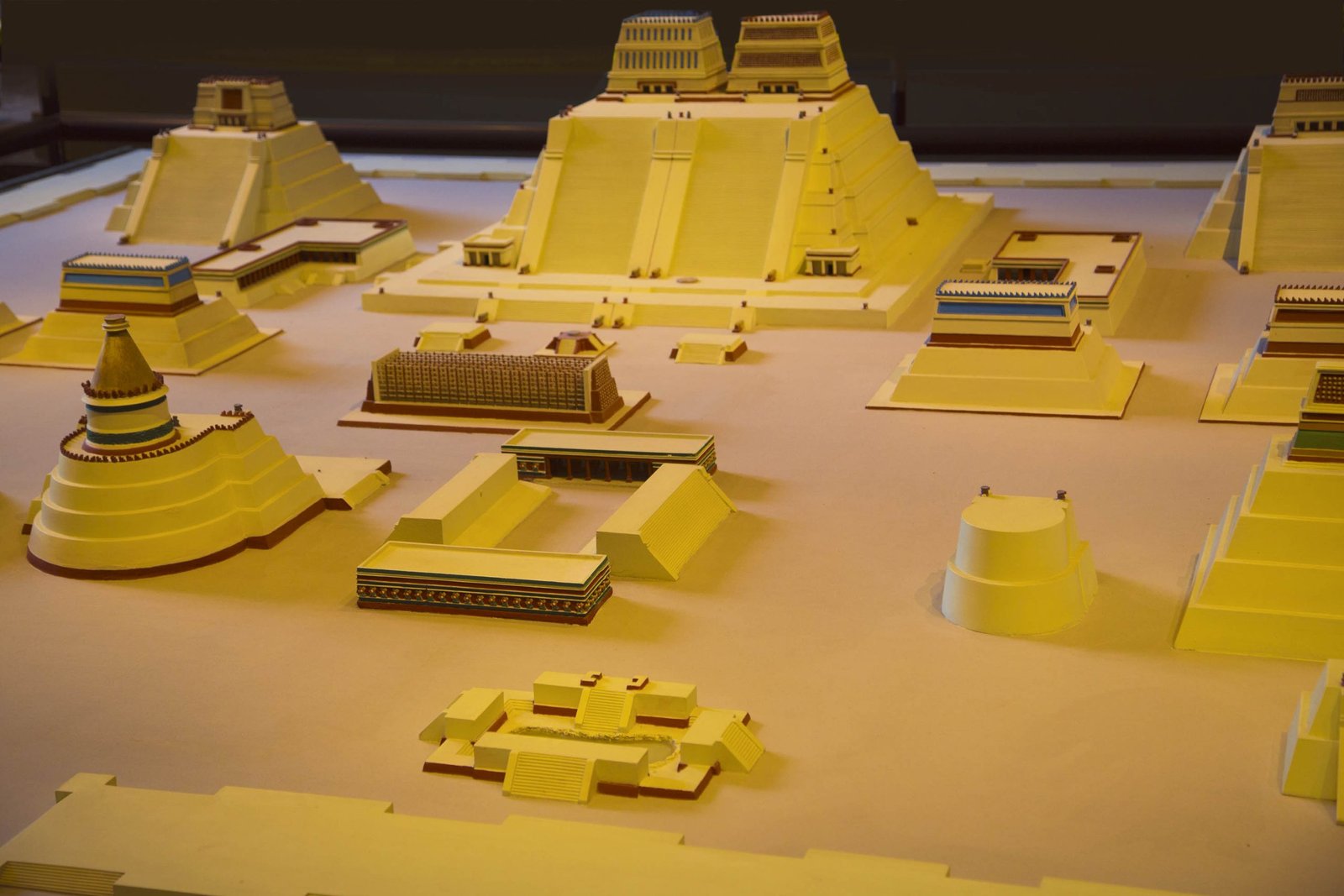

Sacred Precinct of Tenochtitlan

This model was built for the museum’s inauguration. It is based on descriptions by indigenous chroniclers and Spaniards, and images painted in Sahagún’s Los primeros memoriales and the Codex Ixtliltxóchitl. Architect Ignacio Marquina designed the model, consulting Tenochtitlan Council minutes for specifications regarding the distribution of plots among Spaniards.

This model was built for the museum’s inauguration. It is based on descriptions by indigenous chroniclers and Spaniards, and images painted in Sahagún’s Los primeros memoriales and the Codex Ixtliltxóchitl. Architect Ignacio Marquina designed the model, consulting Tenochtitlan Council minutes for specifications regarding the distribution of plots among Spaniards.

Mixtec Codex

Codices are a rich documentary source for information about pre-Hispanic architecture, funeral rites, clothing, plant and animal representation, personal ornamentation, geography, weapons, wars, and many facts about everyday life. The figures represent places, names, dates, foundations, alliances, wars, and successions of different domains. They are unique in that they contain no Spanish elements.

Atlante of Tula

These colossal sculptures represent Toltec warriors standing guard at the Temple of Quetzalcoatl. Each fifteen foot high sculpture is carved from four separate blocks. They were found in Tula (“place of many neighborhoods”), the center of Mesoamerican civilization for many years, ruled by a dynasty of priest-kings, descendants of the god Quetzalcoatl.

Coyote Head

This Early Postclassic (900 CE-1250 CE) piece represents a helmeted man with the head of a coyote, which many scientists believe to be Quetzalcoatl, while others say it is two coyote warriors, demonstrating the link between the coyote and war.

Temple of Quetzalcoatl

One of the walls in the Teotihuacán Room is a faithful representation of one side of the Templo Mayor, or Temple of the Plumed Serpent. The original temple stands at the center of the Teotihuacan citadel built in the third century. The balustrade features large snake heads. Undulating snakes are carved into the sloping sides in low relief, their bodies covered with feathers and surrounded by aquatic motifs such as shells and snails.

Disc of Death

This sculpture was found in 1963 near the Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacan. It belongs to the Classic period (200 CE-650 CE) and represents a human skull with a tongue hanging out, crowned by a glowing circle. It could be related to human sacrifice and the death of the sun.

Chalchiuhtlicue

The goddess of horizontal waters, lakes, and rivers is also known as the Great Goddess of Teotihuacan. This sculpture was taken from the Pyramid of the Moon and is also associated with fertility and agriculture. It belongs to the Classic period (200 CE-650 CE) and was discovered in 1888.

Chac Mool

This renowned sculpture in the Maya Room belongs to the early Postclassic period (900 CE-1250 CE) and represents a powerful warrior. Several of these sculptures are scattered throughout different regions of Mesoamerica and their function continues to spark controversy. They were part of ritual furnishings and most likely used as sacrificial stones.

Colossal Olmec Head

The Olmec people represented their rulers as gods or demigods. Into these heads were carved sunken eyes, thick asymmetrical lips, and other traits of the jaguar-man.

Peopling of America Room

The Peopling of America Room uses models and murals to represent theories about how man came to the New World across the Bering Strait from 30,000 BCE to 2000 BCE.

Lucy

Reproduction based on an analysis of the nearly complete skeleton of an adult female Australopithecus afarensis (approximately 3.2 million years old) found in Ethiopia in 1974.

The Acrobat

Among the most beautiful works of pre-Columbian art, this piece belonging to the Preclassic period (1200-600 BCE) made of fine white clay represents the typical “childlike” facial features of the Olmec people.

Pakal Mask

Inlaid with 340 jadeite tesserae and shell and obsidian eyes, this mask was among the funerary objects found in the tomb of Pakal, the ruler of Palenque. The mask portrays a young face associated with the maize god and belongs to the Late Classic period (680 CE).

National Museum of Anthropology

Paseo de la Reforma, Colonia Chapultepec Polanco, México City

Tel. +52-55 4040 5300 www.mna.inah.gob.mx

Hours: Tuesday to Sunday from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m.

Admission: 4 USD. Free to seniors, teachers, students, children under thirteen, and people with disabilities. Sundays: free admission for residents.

Directions

From North, Central, and South America and the Caribbean, Copa Airlines offers five flights daily to México City through its Hub of the Americas in Panama City.