Tales from Reality: The Lost Token

By: Juan Villoro

Illustrated by Henry González

Selection and Compilation: Carolina Fonseca

In late 2014, my friend Paco had an experience that encapsulates the power and arbitrariness with which time fulfills its promises.

In 1973, Paco was a drummer who discovered rhythm on his mother’s pots and pans and worked at perfecting it on a set of Ludwig drums as patched as our nation’s history. He knew how to make noise with objects and how to remain silent with his friends. While we talked, he nodded, as if keeping time. So rarely did he speak that when he did, we never forgot his comments. One night he pronounced the word “anacrusis” and explained its importance in jazz. Interestingly, his explanation of the notes that precede a musical phrase defined our situation: we were an anacrusis, the prologue of what was to come.

On what was to be remembered as one of those “red letter” days, fate knocked on his door in the form of a friend of a friend of a friend who offered him a job in New York. Paco sold his drums to buy a suitcase and packed in it the dreams of a generation. We accompanied him to the airport with an enthusiasm inflated by our fantasies. To us, the skinny guy in a scarf nervously woven by his mother and long enough to wrap around his neck three times was a budding legend, a possible link to Miles Davis.

His stay in New York was like that of so many musicians, who gain interesting experience without really becoming successful. He returned with tales that would have better served someone capable of storytelling and a diploma that announced a career change from drummer to audio engineer.

But sometimes stories can only be understood long after they happen. Paco returned to New York in December 2014 and discovered something he hadn’t thought about for forty years.

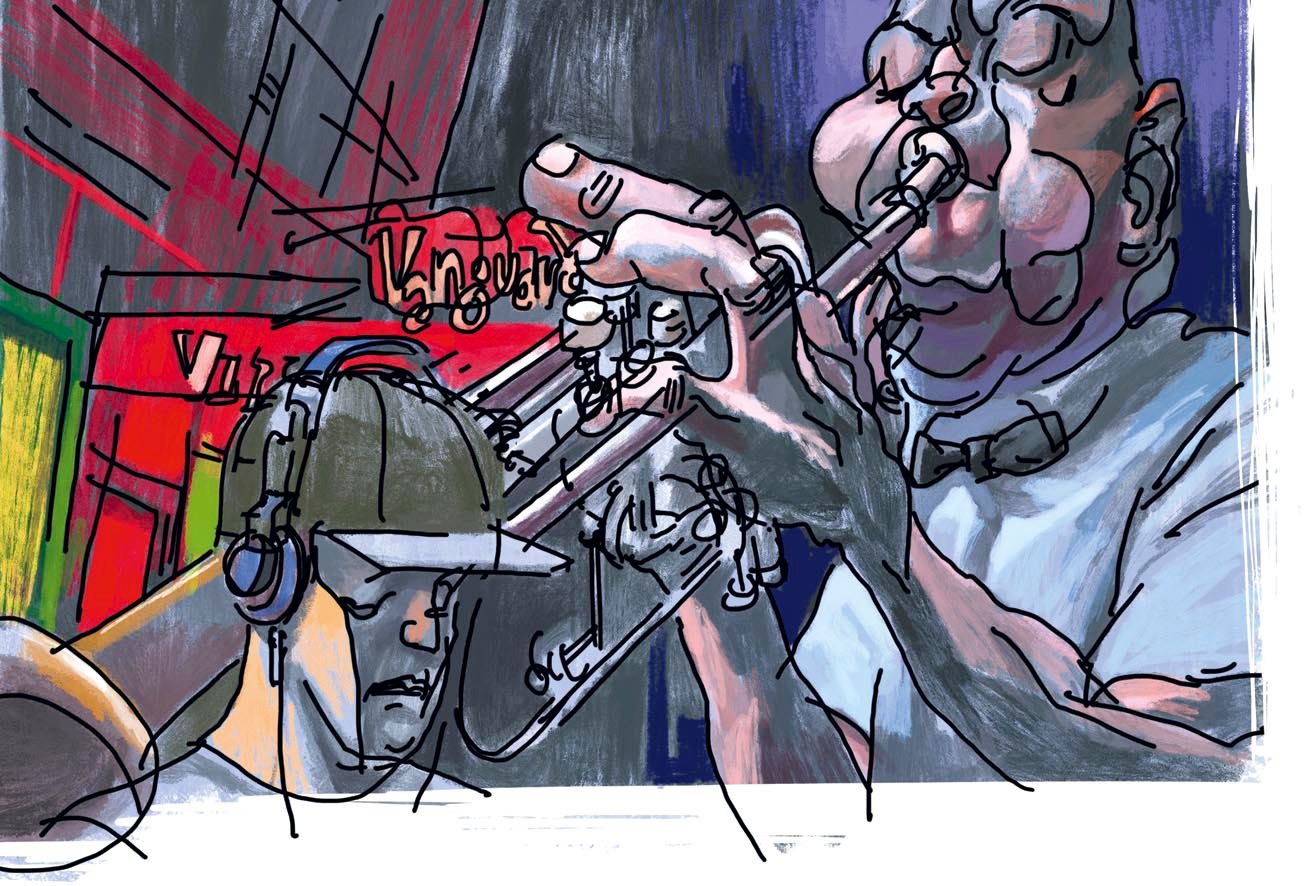

During the time he struggled to survive in that city, he preferred playing to listening to other musicians. Even so, he took a liking to descending the stairs that led into the depths of the Village Vanguard and, above all, to the coat check girl. In the club atmosphere clouded with smoke everything seemed permeated by evanescence. The girl was there and wasn’t; isolated in her cloakroom, she never seemed to enjoy the prodigious sounds coming from the horns; pale and unforgettably sad, she attended to clothes without bodies, arms that couldn’t embrace her.

Paco had sworn to get through the winter with just a Chiconcuac sweater but went out and bought a coat in order to briefly brush her fingers as she handed him his token. In all his romantic encounters –and there were many– my friend always depended on the women to provide the words. There was never any reason for the coat check girl to take the initiative. She remained an unattainable and tenuous presence, like the phases of the moon.

When he decided to return to Mexico, Paco spoke to her for the first time, announcing that he was leaving. She gave him a kiss that was difficult to explain, motivated perhaps by passion, pity, or simple and amazing human kindness.

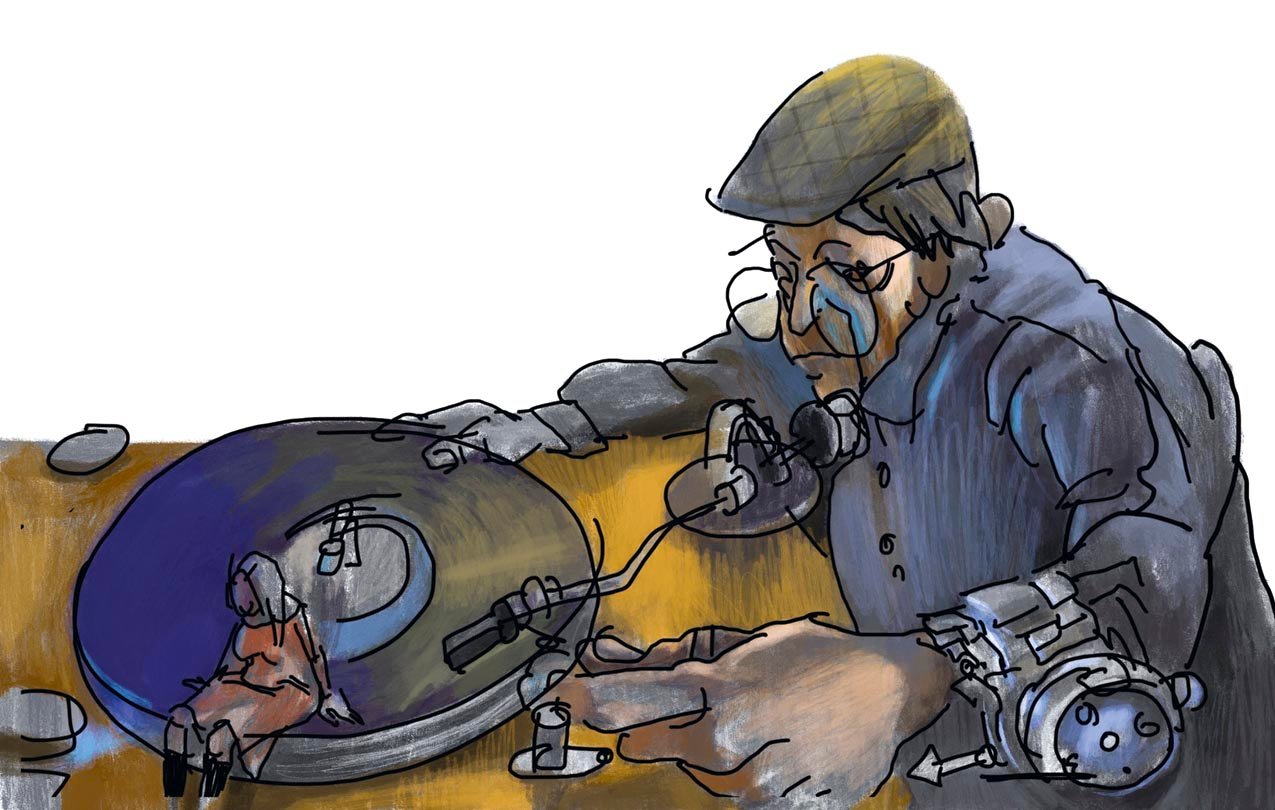

In 2014, my friend returned to New York to celebrate the New Year and went out to hear jazz again, this time at the Blue Note. He stepped up to the cloakroom and handed over a camel hair coat, very different from that first coat he had purchased at a Salvation Army warehouse.

When he was ready to leave at two o’clock in the morning, he couldn’t find his token. He checked his pockets while the attendant stared at him, half kindly and half annoyed. Suddenly he realized why he couldn’t find the token: he was standing in front of the girl from another time, now a grown woman, tired of being where she was. Forty years earlier, the woman had embodied the unattainable virtue of the rain.

Paco remembered that he had left his cell phone in his coat pocket. If he could call it, they could locate it. She lent him her cell phone and Paco dialed the number with the fingers of a retired drummer. The phone rang in the heart of his coat.

What could he possibly say to this woman forty years later? He simply thanked her, walked back out onto the street, and let the frigid air have its way with his face.

A few blocks later, he patted his chest and felt an object. It was the plastic token in his shirt pocket. For a moment he thought about going back to return it, but preferred instead to keep it, like a kind of coin used to buy time.

It would have been nice if his cell phone had rung again inside his coat and better yet, if it were she calling him. But things don’t always happen.

The year went about ending and Paco understood that he had traveled to New York to live an unrequited love, one worthy of a song: “The one that got away, but that I remember,” he tells his friends, in the unforgettable tone of someone who uses very few words.

The Author

Juan Villoro (Mexico City, 1956) is a playwright, novelist, short story writer, essayist, and journalist. He has been a professor at the UNAM and visiting professor at Yale, Princeton and Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, as well as at the Foundation for New Ibero-American Journalism, founded by Gabriel García Márquez. From 1995 to 1998 he directed La Jornada Semanal, a cultural supplement to the newspaper La Jornada. For his body of work, he was awarded the José Donoso Ibero-American Literature Award and the Manuel Rojas Ibero-American Narrative Award, both presented in Chile. In Spain he received the Premio Herralde for his novel El testigo (The Witness); in Argentina, the ACE Award for his play Filosofía de vida (Philosophy of Life); in Cuba, the José María Arguedas award for his novel Arrecife (The Reef); and in Mexico, the Xavier Villarrutia for his book of short stories La casa pierde (The House Loses). His journalism has been recognized internationally by the King of Spain, as well as the City of Barcelona, and Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. His most recent book is El vertigo horizontal: Una ciudad llamada México (The Horizontal Vertigo: A City Called Mexico).