Camino de Cruces: The First Interoceanic Route

By Alexa Carolina Chacón

Photos: Rommel Rosales

Illustration Omar Pérez and Daniela Vanegas

This article takes us into the forests while also explaining how the Isthmus has been destined to connect oceans since the Colonial era. The Panama Canal is a manifestation of this destiny. There, in the humid green jungles of Panama, the Camino de Cruces trail awaits you…five hundred years later.

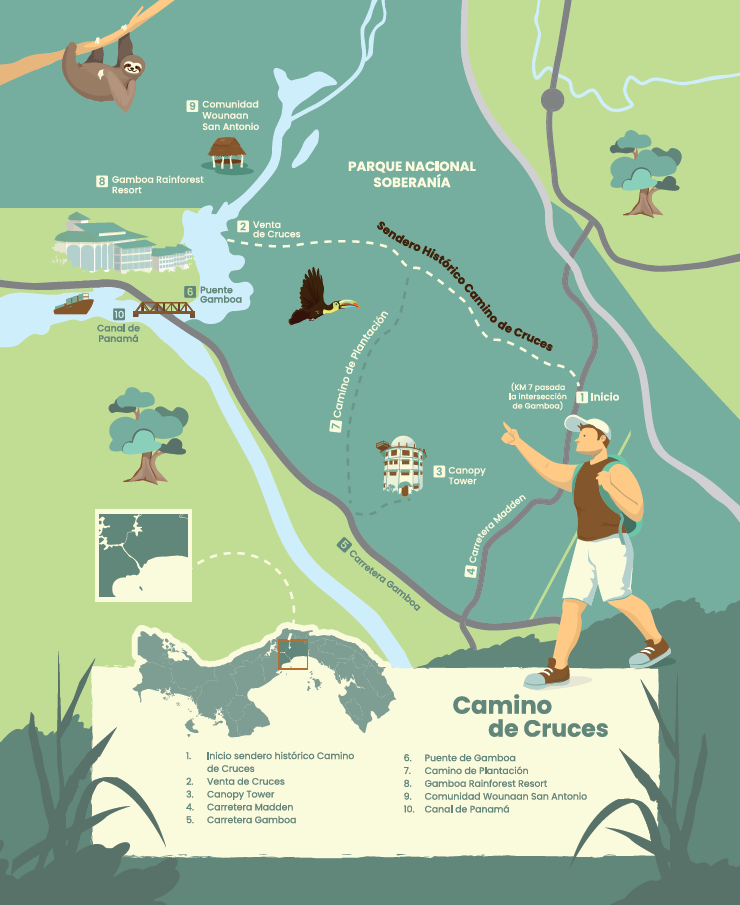

Panama, this slender isthmus —30 miles wide at its narrowest point—was destined by history to connect the world. That future was determined long before the French laid the first stone in an attempt to construct the giant engineering project that is the Panama Canal. The story begins with the 16th century Camino de Cruces, which was built to connect the Caribbean to the Pacific. The Camino Real —which will be featured in a future edition of Panorama of the Americas—transported treasure (especially silver from Perú), while the Camino de Cruces facilitated the movement of people and goods between the original Panama City (what is now Old Panama City) and Portobelo.

By order of Pedro Vásquez de Acuña, then governor of Panama, the road was built in 1527 with round stones known as canto rodado. These stones formed a cobblestone path that still survives on certain stretches of the trail. Mules were used for trekking through jungle environments under difficult conditions that were unlike anything the travelers had known in the Old World. In a time when there was no equipment for leveling roads or dealing with mountain slopes, roads were simply laid wherever feasible. I will say that the nearly seven miles we walked are far from being easy or straightforward. Of course, I had to confirm this fact in person and see the stone trail where it all began.

Let’s Walk!

No one is better at traversing Panama’s difficult trails than Rick Morales. The director of Jungle Treks knows the history of the colonial roads and can identify the concomitant flora and fauna as if they were everyday items, but he also moves through the jungle with an ease that is very reassuring to people like me, who are taking their first steps into the world of hiking.

The Camino de Cruces runs through the Camino de Cruces and Soberanía national parks. Easily manageable trails like Camino de Plantación and El Charco lie nearby. Our intended trail is nothing like those. We start our trek from the Camino de Cruces parking lot on the Madden highway. With his pack already on his back, Rick explains that we will encounter several different elevations and challenges: fallen tree trunks, dense vegetation, mud, and of course, wet stones that require total concentration on both ascent and descent.

On our tour, we saw sloths, anteaters, and white-faced capuchin and howler monkeys.

We start walking and the silence of the jungle drowns out the noise of the highway. Once again, I confirm that Panama concentrates a gamut of experiences in a small area. One moment you’re surrounded by civilization, and the next you’re seeking fragments of history in the jungle. We’re setting out on a six hour trek that will end at Venta de Cruces, on the banks of the Chagres River, just across from the Gamboa Rainforest Resort. The first thing that strikes me is the courage, and yes, the madness, of those Spaniards who colonized these lands. If I, as a Panamanian accustomed to the heat and the mosquitoes, was challenged by this trail, I can’t imagine how they managed.

The Camino de Cruces trailhead is less than half an hour from the city center, proving that one reason Panama is popular as a destination is the variety of tourist attractions close at hand.

Born to the Jungle

Rick strides vigorously and at a pace that demands that anyone trying to keep up be in good condition. Before delving into history, I ask him about his own story. He has been a professional hiker since 1999. Born in Volcán (Chiriquí province), Morales has been passionate about trekking (hiking plus camping) since childhood. He recognizes that it is not a very common activity in the jungles of Panama and Latin America; he was essentially an inadvertent trekking pioneer in this country. He is an expert in little-known routes and is rather possessive of them, not out of egoism, but out of concern for others’ safety: many of the routes require highly experienced guidance.

His favorites are Darién, where Jungle Treks organizes a 12-day expedition; Friendship Park; and Camino Real, which runs from Boquerón to Portobelo in Colón province. He pauses my questions to describe our surroundings: trees like the bongo, the ceiba, the big-bellied ceiba, and the wild cashew. These magnificent trees archive the wisdom of the jungle; they have seen it all. As we press on, short breaks allow us to appreciate the environment. It is not only worth seeing, but worth hearing as well. The bird sounds tell Rick who is visiting us: oropendolas, toucans, trogons, parrots, and a wonderfully imposing rufous motmot that poses on branch in front of me, giving me a good look.

The blue and orange bird is very similar in size to a toucan. As usual, the Panamanian jungle outdoes itself.

Venta de cruces: The Finish Line

The trail is an exciting beginning, but, as anyone who has walked through the jungle knows, it throws up challenges as you go along. As Rick promised, the first stretch of trail is indeed uneven and requires concentration. Some parts are less demanding, but the areas of slippery rock require a degree of proficiency. Our guide is skilled in recognizing mule and cart tracks. He is likewise adept at pointing out the surviving cobblestone stretches. It is easy to see that there was once a road here: the strategic placement of the round stones could only have been intentional.

The expedition boarding the boat at Venta de Cruces, where supplies are gathered before the journey continues to Panama City or Portobelo.

We soon cross the Cabuya and Casaya rivers, which are shallow, as befits the season. It is a good opportunity to refresh our faces and feet; the latter are feeling quite tired in our jungle boots. The rest stops are shorter on the second half of the road: the canal mosquitoes encourage us to keep moving. That’s how I realize we’re nearing Venta de Cruces, a key stopover on the Isthmus of Panama trade route during the Colonial era. Located on the banks of the Chagres River, this site marked the end of the Camino de Cruces and the start of the river journey to the Caribbean. The word “venta” refers to an inn or traveler’s stop that offered food and lodging.

Trek Info

Degree of difficulty: 7/10.

ESSENTIALS

– Excellent physical condition. The trail is difficult, not so much because of the distance, but because of the humidity, the heat, and the uneven terrain.

– Long pants.

– Hiking boots or shoes.

– Walking sticks.

– Water.

– Hat for the river.

– Dry bag for the river.

All that remains are the ruins of a church that could easily feature in a Tomb Raider movie. Who would expect to find that here? Panama reveals some of its secrets to hikers. Once here, I feel a deep sense of pride —as I swat at mosquitoes— in a challenge overcome. As with any Jungle Treks activity, this is not the end. Now comes the river portion of the trek. While the six hours of walking worked our legs, now it’s the upper body’s turn. A boat picks us up for the trip to the Wounaan community in San Antonio, where we have lunch and inflate the dinghies we will paddle down the Chagres River. It’s important to note that this tour doesn’t usually make a stop at the community. If you take the usual tour with Jungle Treks, you will have a quick lunch at Venta de Cruces, where you will also inflate the rafts. A different tour offered by Jungle Treks, which starts on the Pipeline Road, includes a full cultural visit to the community.

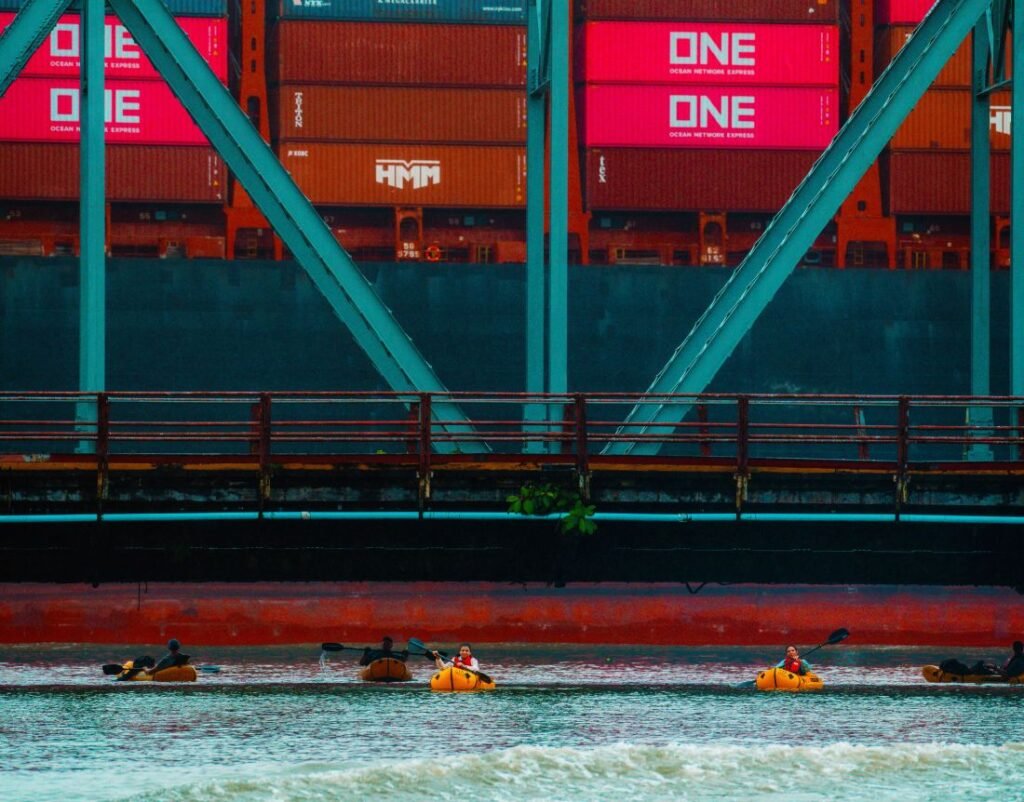

Paddling Down the Chagres River

The next scene is simply surreal. Our boat stops mid-river and we clamber into the dinghies and start paddling toward the Gamboa Bridge. Rick effortlessly coordinates our departure and lunch so that we arrive just in time to watch an enormous ship float by. The aim is to bring the journey to a close with an admirable illustration of the present: modern Panama connects the world with its canal. It’s a poetic metaphor. Duly cautious, Rick allows us to go no farther than the buoys: crossing the Canal is not permitted, nor is it necessary. Even from this vantage point, we feel miniscule in the face of this floating cargo complex.

Where treasure ships once sailed, global merchandise now travels, confirming the truth of what might sound clichéd: Panama is the bridge of the world, and yes, the heart of the universe.

Finally, we arrived at what was once the Modelo Prison, demolished in 1996. In front of it is the Wah Kon Ce Chinese Cemetery, established in 1893, where many of the Chinese workers who arrived in Panama during the railroad construction were buried.

Our tour concludes at Totti‘s restaurant, a retired police officer who has been the chef at this place for more than fifteen years. He welcomes us with jazz music and delicious torrejitas de bacalao (cod fritters).

From his establishment, Efraín shows me the old wall that served as a dam and the fountains known as “los llorones” (the weepers), where female water carriers came to collect water.

CONTACTO

contact@jungletreks.com

+507 6438 3130

jungletreks.com

Seated at Totti’s place, Efraín tells us that, depending on the day and time, the atmosphere of the neighborhood changes: sometimes there is more noise and some days the streets are empty.

If someone is looking for a quiet walk, Monday morning is the best time, but if what you want is to see the neighborhood in its full splendor, the ideal is to come from Friday onwards.

Leave a Reply