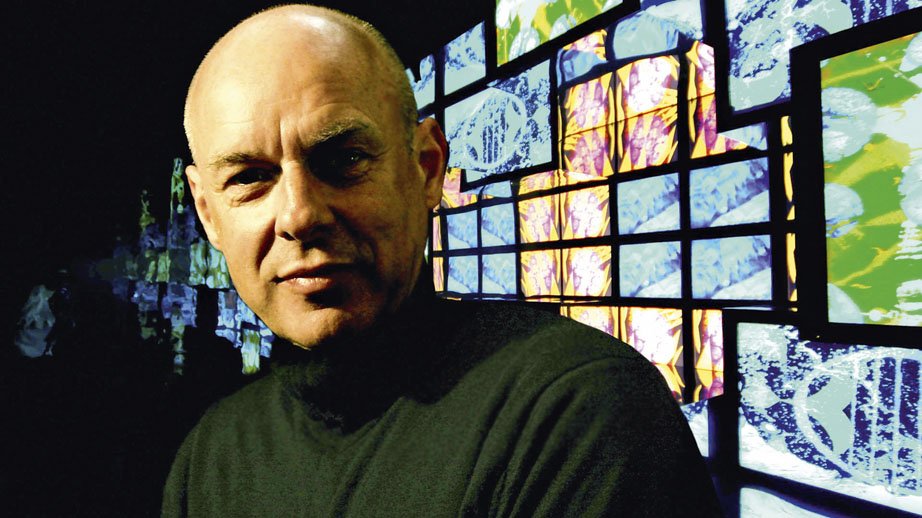

Brian Eno Knows

By Jacobo Celnik

Photos: EFE, Latinstock, Alamy

Brian Eno –a trail-blazer known for revolutionary ideas, novel suggestions, and pushing himself and others outside of artistic comfort zones– is one of the most interesting artists of our time. Continuous change and a multi-disciplinary dialogue that includes painting, literature, and music mark the course chosen by a man who began in the world of pop music without really wanting to be there. In the winter of 1971, when he co-founded the band Roxy Music with singer Bryan Ferry, an interpreter of the nascent glam rock and art rock aesthetic, he did so as a means of expression and a relevant way to experiment with his musical knowledge, rather than as a stable career prospect. Eno was convinced that the recording studio was equivalent to 19th-century orchestras, in other words, a space where he could experiment without limits or pressure. Just for a moment, let us imagine a young man of twenty, a fan of John Cage, Erik Satie, Arnold Schönberg, and concrete music, giving a concert in which he repeats the same note three thousand times.

He contributed to Roxy Music’s first two works, released in 1972 and 1973. YouTube has a curious clip from an August 1972 episode of Top of the Pops in which the band plays “Virginia Plain” for a handful of spectators on the show’s set and for millions more in the television audience across England. The camera focuses on singer Bryan Ferry for most of the three minutes. Eno, working a Moog and an oscillator, appears for a few seconds in a wide shot of the whole band. They focus directly on him for just an instant to zoom in on the worn silver gloves he wore to bring each Moog note to life. After this performance, Eno decided he would never be put in such an uncomfortable situation again.

“I decided not to do any more live shows, since I felt like that limited opportunities for the experimentation I wanted to do. I did only a few live shows with Roxy Music. One of the reasons is that many factors make a concert the wrong place for listening to the type of music I wanted to create. For example, I didn’t think it was music I wanted to hear in the company of thousands of people. I couldn’t imagine playing my music from those first studio works before an audience of 20,000 people. A live show has more to do with introspection and being alone than with being surrounded by a crowd, which by the way, is truly thrilling,” remembers Eno in his London studio.

This video and several others from the era leave the impression of a battle of egos between Eno and Ferry; in his book, The Thrill of It All, guitarist Phil Manzanera confesses that their agents added fuel to the fire. What started as a wonderful marriage between artists finally broke up on July 2, 1973, when the keyboardist left the group. On stage, Eno made an impact with his extravagant costumes and make-up, while Ferry attracted attention with his looks and stage presence. Eno decided to leave, since his ambitions went beyond conquering masses of groupies. The media tried to exploit the back story of his departure, but Eno was very careful in his public statements. He never said more than necessary out of respect for his fellow band members and a desire not to hurt their feelings. He preferred to speak through his music. “I don’t want to blacken the reputation of the band to benefit others or certain interests, like those of the media. Honestly, I get along well with the band. There are no problems with Bryan; I respect him a lot,” said Eno to Melody Maker in July 1973.

In November 1973, Eno collaborated with the leader of King Crimson, guitarist Robert Fripp, who was on a break after a series of concerts with the band. Eno found the recording studio to be the ideal vehicle and instrument for creation and experimentation. This meeting between an ex-pop star and a guitarist who was exploring new musical possibilities culminated in the album No Pussyfooting, a work not understood by music critics at the time (Eno says it was not intended to be), but which later became a cult classic. Fripp explained: “It isn’t a mass market album, but it will be considered a classic in time. I’m sure that in five years, people will ask why they didn’t appreciate such a quality work back then.” On the album, Eno recorded a series of sounds made by Fripp, which were then modified and manipulated through track dubbing and delay and loop techniques. This was not especially novel, since years earlier artists like U.S. musician Terry Riley (A Rainbow in Curved Air, 1969) experimented with these techniques, as did The Beatles and The Beach Boys, among other bands in the late 1960s.

“My relationship with Fripp began more or less by accident because we both had the same agent. I met Fripp, I liked what he was doing, we got along well, and we had similar personalities. One day I said to him, ‘I’ve been recording some new tapes at home; you should come by and hear them.’ So he came, plugged his guitar into the sound system where the tapes were, and we ended up with No Pussyfooting.” The interesting thing about the process Eno and Fripp used on this album was the type of sound they achieved, a sound based on repetition. The search for sound through notes that bore no relationship to the melody or harmony gave the album its iconic character.

Attempts by critics of the day to categorize or pigeonhole the album led to it being associated with German electronic music, particularly Tangerine Dream and Cluster. But No Pussyfooting was the album that allowed Eno to establish a brand and a sound identity as a producer that was distinct from the aims of krautrock (a word used to describe German music in England). Between 1974 and 1978, Eno permitted himself the luxury of experimenting with a variety of recording techniques and artists in ten studio works. During this time he did not go near a stage. “I think it’s very difficult to make ambient music in a concert setting. People have to get dressed, they have to go out, and sometimes they have to pay a lot of money to sit and listen to you. I don’t think it’s the right place for an ambient experience.”

With all the time in the world and with no pressure to produce commercially-viable albums, each project he undertook benefited from painstaking production and experimentation in collaboration with colleagues and old friends like Bryan Ferry. Here Come the Warm Jets (1974), Taking Tiger Mountain (1974), Another Green World (1975), and Ambient 1: Music for Airports (1978) made Eno famous enough for other artists to take notice of his talent. One artist who noticed was David Bowie, with whom he worked on the albums known as the Berlin trilogy: Low, Heroes, and Lodger. The B side of Heroes (1977) features four instrumental cuts, two of them, “Moss Garden” and “Neukoln,” composed by Bowie and Brian Eno.

“David Bowie was very good at hearing and expanding things, and combining individual parts into a greater whole.” He was already a big success when I worked with him at that time. He could have continued being Ziggy Stardust or the White Duke if he wanted to, but he wasn’t interested in that. I think he was always a move ahead of the game, and every time people thought they had him figured out, he went in a different direction. It was his most characteristic trait, one he preserved to the end.”

After experimenting with German krautrock musicians, in 1979 Eno once again united with Fripp for the work Exposure, a kind of multi-national musical effort that included musicians like Peter Hammill (of Van Der Graaf), Peter Gabriel, Tony Levin, Daryl Hall, and Phil Collins, among others. Later, Talking Heads singer David Byrne invited him to collaborate on three of the group’s albums: More Songs About Buildings and Food (1978), Fear of Music (1979), and Remain in Light (1980), all produced by Eno and on which he also played various instruments. His excellent productions with Talking Heads encouraged other artists, such as Paul Simon, John Cale, Devo, and U2, to ask him to produce their works. Eno was the force behind the success of The Joshua Tree (1987) and Achtung Baby (1991), possibly two of U2’s greatest works, as evidenced by the awards they won.

“On the whole, it was a great relief to go outside my comfort zone. I went from working with silent people sitting in chairs to working with people who were enjoying what they were doing.” They laughed, experimented, and enjoyed the moment. I felt much closer to the German musicians, to Byrne, Bono, Bowie, and others, than to most of my English friends because, in a certain sense, we had traveled the same road: trying to make rock from an experimental perspective.”

Between installations and sound events, Brian Eno still has time to offer opinions on politics and write current events columns. He likes new technologies and, in answer to the fusillade of criticism against the industry for its lack of creativity and innovation, Eno says: “Good music is repetition.” He may have meant it literally, or as an allusion to No Pussyfooting or some of his minimalist works. Only Eno knows.