Wings of a Lioness

By Sol Astrid Giraldo E.

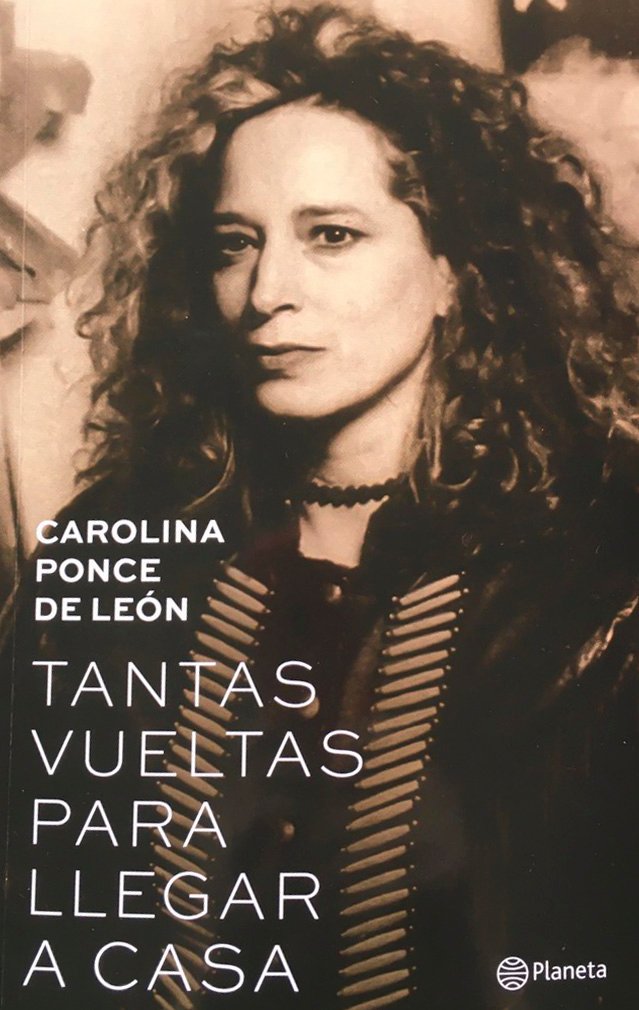

The story of our lives is just that: a story, and it is up to us to make sense of it. There is no pre-established script; that gets written after the fact…We witness Colombian curator and critic Carolina Ponce de León undertaking this process of sense-making in her recent book, Twists and Turns on the Way Home, which is an autobiography, a confession, a reckoning, and a tale of self-rescue. Although she is aware that “a broken mirror cannot be glued back together,” her sense of perspective allows her to search through the threads of her life, stretching them taut as she gathers up the fragments scattered across years and different countries. She weaves together her loves, achievements, and mistakes with private palpitations and the tremors she witnessed in the front-row of the Latin American art scene, which is a fundamental part of her existence.

We readers observe her in different lights. First, she reveals her original wound as the daughter of secret adultery. Her powerful father never recognized her, but life with her diplomat mother offered all the stimulating possibilities of New York City in the 1960s. Next, we observe her constant changes: from the child who didn’t want to live out of a suitcase, traveling from country to country, to the schoolgirl who bowed before her magnificent Parisian teachers. We see her as the adolescent in Belgrade who discovered her body in the arms of a golden boy and again, uprooted and hoping to invent her roots in a Colombia she discovered only as an adult. We see her as the young woman anxious to breathe in freedom and the creator who knew that art was the place where she’d find it. And again, as the “broken mother” who fled to Europe to escape her husband’s abuse.

She makes no distinction between the personal and professional spheres and, instead of writing an academic text about her remarkable career, she illuminates it with the passionate colors of life. This is the book’s principal aim: to entwine her explorations as a woman with those of the curator, critic, cultural powerhouse, and artist. The story encompasses her trials as a young woman abused in her own home, her struggles to forge a place for herself in the male-dominated art world, the stigma she carried as an illegitimate child, and the Eurocentric establishment’s mistrust of “bastard” Latin American art. Her search for her identity parallels Latin America’s search for its own identity; from her first curatorships, she worked to draw both into the light.

© Pablo Salgado, Bogotá.

© Pablo Salgado, Bogotá.

Having played a leading role in the birth of regional contemporary art, Carolina offers an insider’s first-hand testimony. The emblematic “Ante América” exhibition, which she curated with Cuban Gerardo Mosquera for Colombia’s Central Bank (Bogotá), was among the first exhibitions to question the exoticism of modern Latin American art. Staged in 1992, during the sugar-coated sesquicentennial commemorations of the arrival of Columbus in America, the exhibition offered an alternative, baring its teeth to ward off any meek denials. The works of Cherokee, Puerto Rican, Chicano, and Antillean artists, along with the silhouettes of Cuban-American Ana Mendieta, the ritual photographs of Brazilian Mario Cravo Neto, and the spiritualized body of Colombian performance artist María Teresa Hincapié, among many others, presented an America seeking decolonization. Instead of an aesthetics frozen in time, these works delved into economic contradictions, racial tensions, migrations, gender breakdowns, and troubled times. The exhibition marked the end of Carolina’s time in Colombia, but reaffirmed her interest in emerging political art.

2017. Exhibition La Vuelta, International Meetings of Photography, Arles, France.

2017. Exhibition La Vuelta, International Meetings of Photography, Arles, France.

She returned to New York to see what was happening from the perspective of the “epicenter of the center.” As curator of the Museo del Barrio, she witnessed the tensions between Puerto Rican artists, Latinos residing in the United States, and artists working in their home countries. This context helped her understand the fluidity and complexity of the concept of “Latin American art,” as well as the genre’s increasing appeal in auction houses, a commercial success that stood in contrast to its critical and rebellious origins.

After New York, Carolina, who was always careful not to allow herself to be institutionalized, traveled to San Francisco, where she set up her headquarters at Galería de La Raza, a space as small as it was legendary. There she explored Chicano art and added another thread to her skein. She familiarized herself with bicultural iconographies, such as Yolanda López’s “Virgen de Guadalupe en tenis” (“Virgin of Guadalupe in Tennis Shoes”), in which traditional Latino imagery intersected with the aesthetics of gringo popular culture, comics, and graffiti. She promoted art on the streets in a vibrant community where art was not just for museums, but a vibrant activist tool. This period was also permeated by her artistic-romantic relationship with the legendary performance artist, Guillermo Gómez-Peña, with whom she immersed herself, without a lifeline, in the visceral, fractured labyrinths of the Latin American body. In 2013, Carolina went back to Colombia, where she continues to map the pan-Latin American art she loves with exhibitions such as “Referentes.”

2018. Together with the artists Karen Paulina Biswell and Juan Pablo Echeverri at the opening of La Vuelta, Museum of Modern Art of Medellín.

2018. Together with the artists Karen Paulina Biswell and Juan Pablo Echeverri at the opening of La Vuelta, Museum of Modern Art of Medellín.

This book offers the personal vision of a rebellious and curious woman with “mercurial wings,” who has no qualms about leaving a love or a job that becomes dull, a woman who knows how to let go and start over from scratch, how to doubt, consider, look the marginal in the face, and risk the unknown. When writing of private matters, she transcends the personal to describe other periods in history that were not so kind toward women, often lending her most intimate stories an air of social criticism. She uses her own life to portray a generation of women that had no access to the physical, symbolic, or legal resources that have emerged in recent years, women who were not able to speak out against physical or psychological violence, who couldn’t weigh in on the dilemmas of abortion, sexual freedom, alternative maternities, or even the marks of time on their bodies, women expected to endure their lives in silence, laden with the guilt of never achieving the unattainable. Carolina’s is a sincere and passionate voice –argumentative at times, but open-minded, with no desire to preach, either in her personal life or in the art world– a voice that has become the testimony of an era. It is a voice worth listening to as, undoubtedly, we will hear ourselves in it.