A Multi-Cultural Approach to Death

By Juan Abelardo Carles

Photos: Javier A. Pinzón

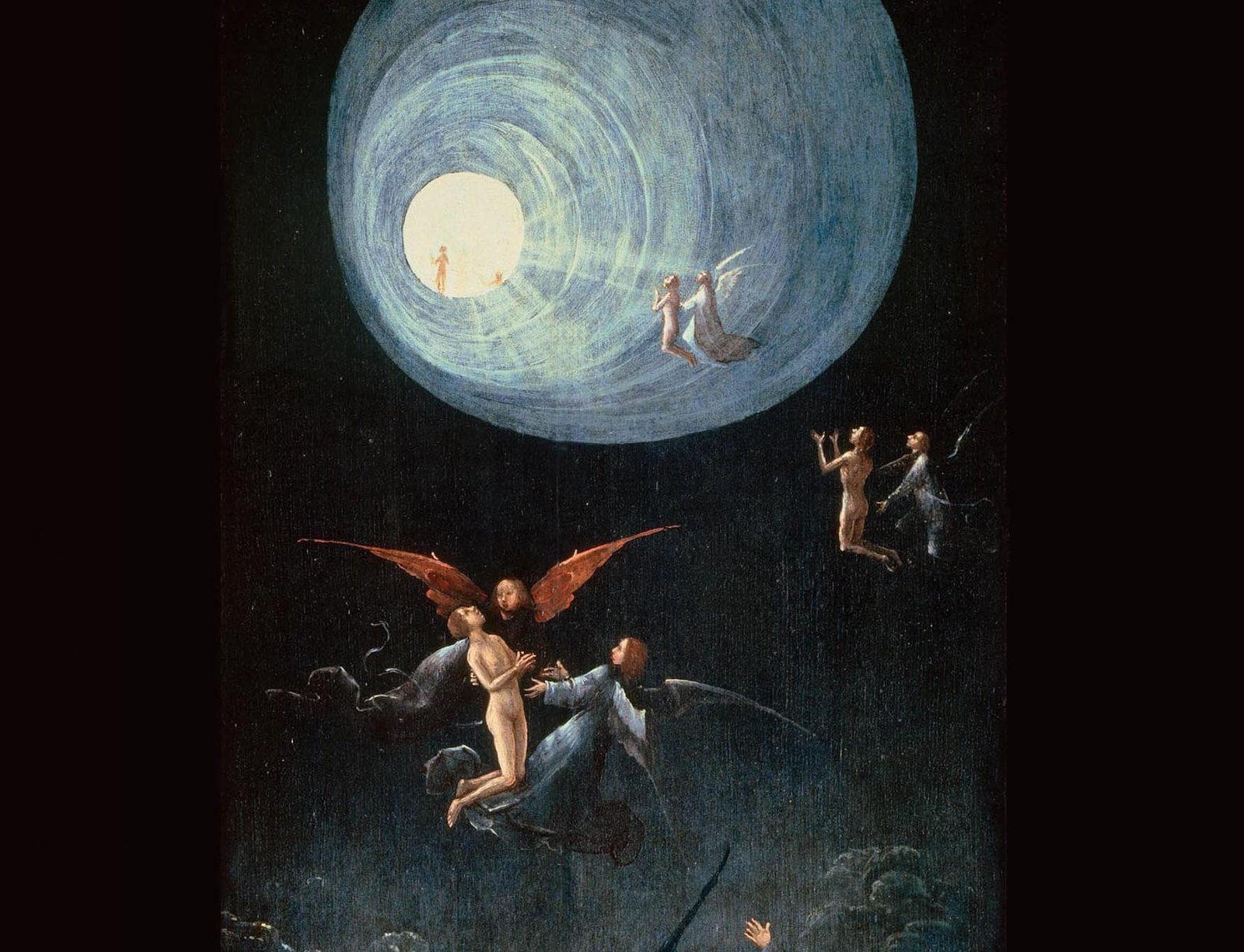

What is death? What happens when we die? What lies beyond? No element of human existence has generated as much anxiety, questioning, and reflection as the end of life. If we understand the rise of religion as a way of grappling with the most profound mystery a person must face, literally overcoming death and continuing on to another stage of existence (or simply ceasing to exist), we will also understand why countless cultures, civilizations, and empires have emerged, risen, clashed, and fallen while defending or combating perspectives on death.

Panorama de las Américas examines this concept that haunts humanity, exploring how it shapes our lives; we take a look at the subject through the eyes of people of different genders, religions, and origins.

Simión Brown Rivera is a Guna cultural researcher and historian. Here he paraphrases reflections on death complied by Dr. Aiban Wagua in his work In Defense of Life and Harmony, which addresses the spirituality of this group of people who live between Panama and Colombia.

We all die, we all depart, leaving this world behind. The river endures, but the footprints we leave on its banks disappear. We will forget the refreshing feeling imparted by the winds that blow in these lands. This thought was shared by a great Nele (seer), Ner Sibu, who lived in Gabdi Diwar (now known as Capetí), on the Tuira River. Everything will be different. It pains us, since we don’t know what awaits us. Lying in a hammock or a bed, we say our last goodbyes to the loved ones who have come to cry over us.

We are made to mix our blood with the earth. We walk on the earth and the earth will enfold us; our blood will be its blood. Our bones, our blood, our hair will become one with mother earth. Dust we are and to dust we shall return.

Swami Nityananda is a mahamandaleshwar, which means he is a member of a monastic order dedicated to preserving and propagating Vedic teachings. Founder of the Shanti Mandir Movement, Nityananda works with young people and disadvantaged groups and promotes initiatives for health and the empowerment of Indian women. www.shantimandir.com

Our belief system comes from Hinduism and was traditionally called Sanatan Dharma: “That which lasts forever.” Everything is a manifestation of the divine, including the human being. Since the divine consciousness exists inside everything that has been born or created, it can trigger the effects of every thought, word, and movement from many previous lives. This is known as “karma.” The supreme aim of human life is to recognize its divine nature and eventually meld with the absolute. Birth and death are therefore ephemeral events in the evolution of the soul.

We should perform the tasks necessary to honor the gift of life, while remaining aware that it is fleeting. As a spiritual leader, this is the main idea I share with everyone. We should all remember that the birth of a human being is something precious and worthy of our full attention, inner contentment, and care. All beings should be content.

Iya Janina Walters is an Ifa Orisha priestess, spiritual life coach, and practitioner of Healing Arts by Iya Janina. She is representative for Latin America at the prestigious Ancestral Pride Temple in the city of Ota, state of Ogun, Nigeria (Fasola family line), and an ordained priestess privy to the mysteries of Ifa, Egbé, Shango, Oshun, Nana, Iyaami Oshoronga, and Ogboni. www.iyajanina.com

Death is a change and a transition toward another energy reality: the astral world. Birth is our dawn and death our twilight. People fear the night and what they cannot see with their external vision, when in reality, the two worlds are in equilibrium. Nothing dies; everything transforms because everything is energy and to “see” and understand the astral world, we need to learn to feel and use our internal vision. Ancestors represent a third of the power in Ifa Orisha philosophy, a spiritual system with some one hundred million followers that is indigenous to the Yoruba kingdom of western Africa. It teaches us to feel and maintain our equilibrium through the forces of nature (Orishas) and the astral world, which is the repository of ancestral wisdom.

There is no fear of death, but there is a fear of dying before we fulfill our mission or purpose in life, which is why we need to balance our physical world with our emotional and spiritual world. Heaven is our home; the earth is the marketplace of life, where we come to learn, which is why we do not believe that anyone comes to earth for a holiday. When we die, we can finally go home and add what we have learned to the already extensive accumulation of ancestral wisdom. Iba Ara Orun Kinkin! Glory to our ancestors, inhabitants of the heavens, our home.

Gustavo Kraselnik is the rabbi and spiritual leader of the Kol Shearith Israel Synagogue, the oldest in Panama. Drawing on a liberal and progressive approach to Judaism, he has been effective in fostering inter-religious and multi-cultural dialogue. (Kol Shearith Israel, on Facebook and Twitter).

It is paradoxical, but death is presented as both a mystery and a certainty. It is a mystery since we do not know what happens after it occurs (the Jewish tradition has a variety of opinions about it), and a certainty because we know that death is a inevitable part of our fate. Given that this is one mystery we cannot solve, we would do well to focus on the certainty. Recognizing that we are mortal, knowing that our passage through this world is brief, we must try to live a meaningful life.

From this perspective, death is what gives meaning to life. The finite nature of our existence makes every moment a unique and unrepeatable experience and as such, we should embrace it, dedicating time and effort to truly transcendental things like affection, personal development, and building a better society and world. Nonetheless, death is not the end of life. Beyond personal beliefs, we know that we will live through our descendants, the love and memories of our loved ones, and the legacy we leave behind. We should aspire to have a life that is sufficiently fulfilling that when our “time to die” (Ecclesiastes 3:2) comes, we can tranquilly return our souls to the creator knowing that we have done our duty.

Bernardo Stamateas is a Baptist pastor, clinical sexologist, and PhD psychologist. A prolific writer and conference speaker, he focuses on personal development and the analysis of different types of toxic human relationships and how to deal with them. www.stamateas.com

Humans are the only beings in creation aware of their own deaths. It doesn’t matter whether we exercise or eat healthfully, we still die. Death is impartial and universal. Death usually awakens fears about how we will die and what will happen afterwards. Some people wonder whether they will go to heaven or hell. Others do not believe there is anything after death. For those of us with faith, death is simply a change of vessel: we leave our bodies and enter the presence of God.

The great writer Victor Hugo said: “I have not died; I will go back to work in the morning.” Only when we have faith in this life and in the beyond, can we see death as a parenthesis, not an end point. Our fear of death completely disappears when we have the surety of finding ourselves not before a wall but rather a door to the better dimension that is eternal life through Jesus Christ. We believers accept the message of Jesus, who said: “Whoever believes in me, though he die, yet shall he live.” Ideally, death should not make us afraid, but allow us to ponder the life we decide to live here and now. So, let us choose an earthly existence filled with unconditional love, positive words, and big dreams.

Diana Marcela Gómez is an agnostic anthropologist who holds a Masters from the National University of Colombia and a PhD from the University of North Carolina. A teacher and researcher, her work is focused on violence, armed conflict, feminism, and the evolution of gender perspectives.

I see death as part of life; the two constitute a single sacred cycle. While I don’t believe in the beyond or heaven or hell, I understand that we are elements of the universe and types of energy and I think that this energy retains a material form even in the absence of a physical body. I believe that the dead have agency, in other words, they can act and affect lives, not only through the kinds of relationships they forged in life, but also because their energy is still present.

In an investigation into disappeared and murdered persons in the context of socio-political violence, I was able to see how human beings are connected beyond mere physical presence. The bodies of men and women are not discrete units but rather porous ones that communicate beyond physical language. In some indigenous and Afro-descendant communities, dreams are a channel of communication with the dead. While Latin American societies have tended to reject these philosophies, they dominate the way we relate to death. By this logic, the dead are the ancestors who always walk with us, thus re-creating a relational society rather than an individualistic one like capitalism. Given that life and death are sacred, the violent disruption of life can lead to strong imbalances in society.