Giving Young People Tools to Build Their Futures

By: Juan Abelardo Carles

Photos : Javier Pinzón y Cortesía RET

Eduardo is 25 years old and resides with his family –his parents and five siblings– in the Las Piedras community, near the Ecuadorian city of Esmeraldas. As a member of the Young Social Replicators of Esmeraldas (JORES is its acronym in Spanish), he organizes training activities for young people from Las Piedras and other informal communities in Ecuador. “We’re currently working on the problems in San Lorenzo, where there was an explosion, focusing on children and adolescents, addressing different topics in a project sponsored by UNICEF,” he explains.

He is referring to an attack in a town near Esmeraldas, in which a group of FARC dissidents detonated an explosive device in front of a police station. Many of the local residents are Colombians displaced from their country by violence, who arrived in Ecuador in search of peace. Seeing themselves affected once again by violence disturbed everyone, especially children and young people.

“We teach them life skills, addressing topics such as gender, sexuality, equality, rights, xenophobia, cultures of peace, discrimination, values, and resilience, to name only a few of the things we cover,” explains Eduardo. JORES is an excellent example of the kind of groups that have emerged in the region under the umbrella and guidance of RET International. The group has been working for more than 17 years in areas where political conflicts or natural disasters have rendered the population vulnerable to impermanence, overcrowding, and lack of opportunities.

RET is present in crisis regions from the Middle East to the Far East and Africa to Latin America. RET’s work in the latter region has been essential, especially in Central America and the northern part of South America, where crises of human mobility (generating migrants and refugees) seem to have become chronic. According to Colombia’s Registry of Victims, armed conflict has displaced 7.3 million people since 1985, both inside and outside the country. Meanwhile, UNHCR estimates that more than three million Venezuelans have been forced out of their country, a figure that is estimated to reach close to five million over the next five years. Elsewhere, 3.5 million Central Americans have immigrated to North America, according to a study presented by ECLAC and FAO in Marrakech last November.

RET staff members point out that refugee status carries an additional risk for young people and children, beyond the other precariousness they face: “Families granted refugee status receive humanitarian aid, space in a shelter or refugee camp, food, and basic healthcare, but their children and young people suffer the interruption of their educational process. And this gap occurs at the height of their development and growth, when their creative, physical, and intellectual powers are at their peak. This need may seem less relevant to survival, but in fact it is essential. RET works to fill that gap.”

How do they do it? Roberto, also from JORES, sums it up from a young person’s perspective: “We begin working on activities with young people and present RET with a proposal so they can decide how to help us,” he explains. Proposals must include details regarding schedules, budgeting, work teams, assistants, and other factors. “Over the course of a year, we can schedule five principal activities, which start with training from RET at the beginning to improve our knowledge and help us use our tools by teaching, for example, life skills and ways to reduce risks from discrimination, violence, and xenophobia, and providing information on LGBT issues as well as recreation,” continues Joan.

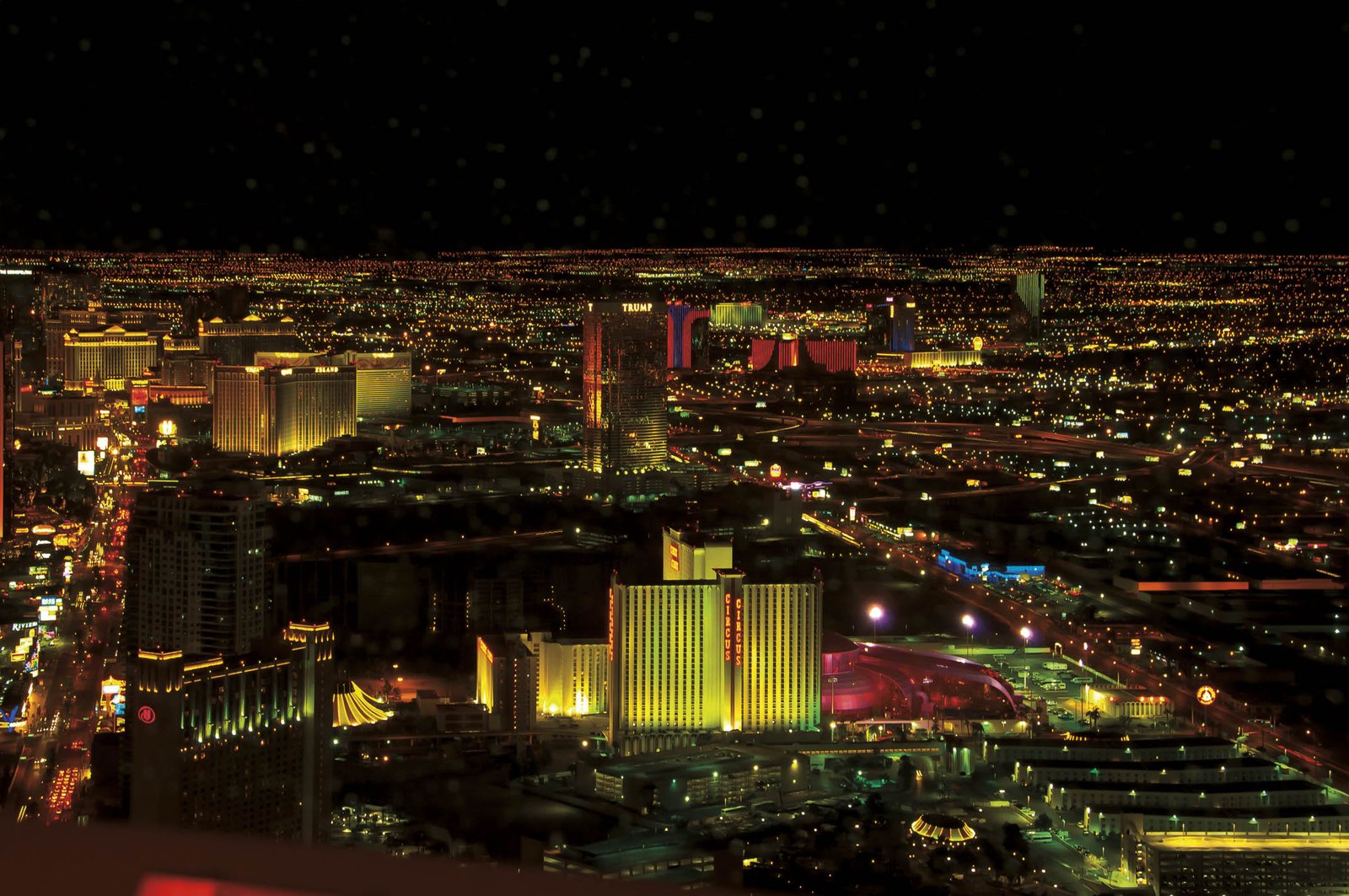

RET’s methods for incorporating young refugees into the processes of building their futures have proven to be so effective that they are being applied to other young people in other fragile environments. In Panama, for example, Cristina and Ricardo work with the Juventud Activa y en Progreso (JAP) organization on initiatives that help prevent school dropouts in the San Miguelito area, one of the most populous neighborhoods in the Panamanian capital. The RET’s intervention has proven a watershed in his life.

Ricardo used to spend hours on social networks and chatting on his cell phone. He would do homework when he felt like it: “I had nothing to do and no idea how to use my time, but as soon as RET arrived, they began to help many young people, including me. They challenged some of my behaviors, helped me to become a leader,” he explains. Young Cristina was drawn to the dangerous world of gangs.

“It was hard to walk down the street; you’d be afraid of the gangs and it seemed preferable to join them before anything happened to you,” she recalls. Those fears disappeared when she joined JAP: “I talked to the gang members and told them I couldn’t hang out with them anymore and they told me they’d leave me alone,” concludes Cristina.

The JAP dynamic includes, first of all, an educational component, helping young people, especially those doing poorly, to remain in school; an athletic component is next, focused on tournaments and intra- and intercollegiate championships; followed by a cultural initiative, with an emphasis on stage and fine arts performances. For example, while Ricardo participates in football tournaments, Cristina enjoys designing and painting murals.

The influence these RET-sponsored and driven groups have on young people is so profound and positive that sooner or later the children’s family environment begins to change.

In the community of Gran Sabana, for example, located in San Francisco, in Venezuela’s southern state of Zulia, the Lazos de Amistad project works with children to keep them from falling into drug use, sexual abuse, and early pregnancies, among other risks. Nora, for example, belongs to Lazos de Amistad and participates in an initiative called School for Parents.

The School for Parents helps to develop communication skills among family members, to increase understanding, confidence, and feelings of trust between parents and their children, who then stay closer to their families and off the streets.

“RET seeks to stimulate and develop the resilience of young people through education, training them and providing the tools that allow them to become stronger human beings and potential transformers of the future of their communities and their country,” explains Ruth, another collaborator. In summary, RET is creating leaders.

This objective is clearly visible in Ciudad Belize, the capital of Belize, where RET sponsored the creation of the Youth Leadership & Advocacy Network (YLAN, for its acronym in English). Eighteen-year-old Michael works with YLAN and RET in the communications area. He also studies English at the University of Belize. “At YLAN I work with women and young people aged 14-35. Young people have an innate potential to develop leadership skills. We use RET support and intervention to release and channel that potential, through the empowerment that education provides,” he says.

The transformation processes experienced by these young people, along with the self-confidence they develop thanks to the RET facilitators, is such that they often conceive of initiatives and seek to undertake them independently or become facilitators in other RET programs for the kids who come after them. For the RET protection program group in Panama, it’s about “giving them a break and stepping back a bit, because they’ve already been given the tools they need to move forward. The idea is not to create dependents, but instead agents for change in their community.”

And it seems to be working. Nora wants to study advertising and create a foundation to help replicate in other communities what they achieved in their own with the help of RET; Eduardo is thinking the same thing: “In any case, we want to become independent from RET and create a stronger group capable of generating our own training and finding a way to legally establish the group as a social and youth activist program.” Cristina wants to study criminology and Donald hopes to form a family. And unlike many young people in risky social situations, they have a chance to achieve their dreams. www.theret.org

*The names of these teenagers have been changed for their protection.