Luis González Palma: The Body’s Resistance

By: Sol Astrid Giraldo

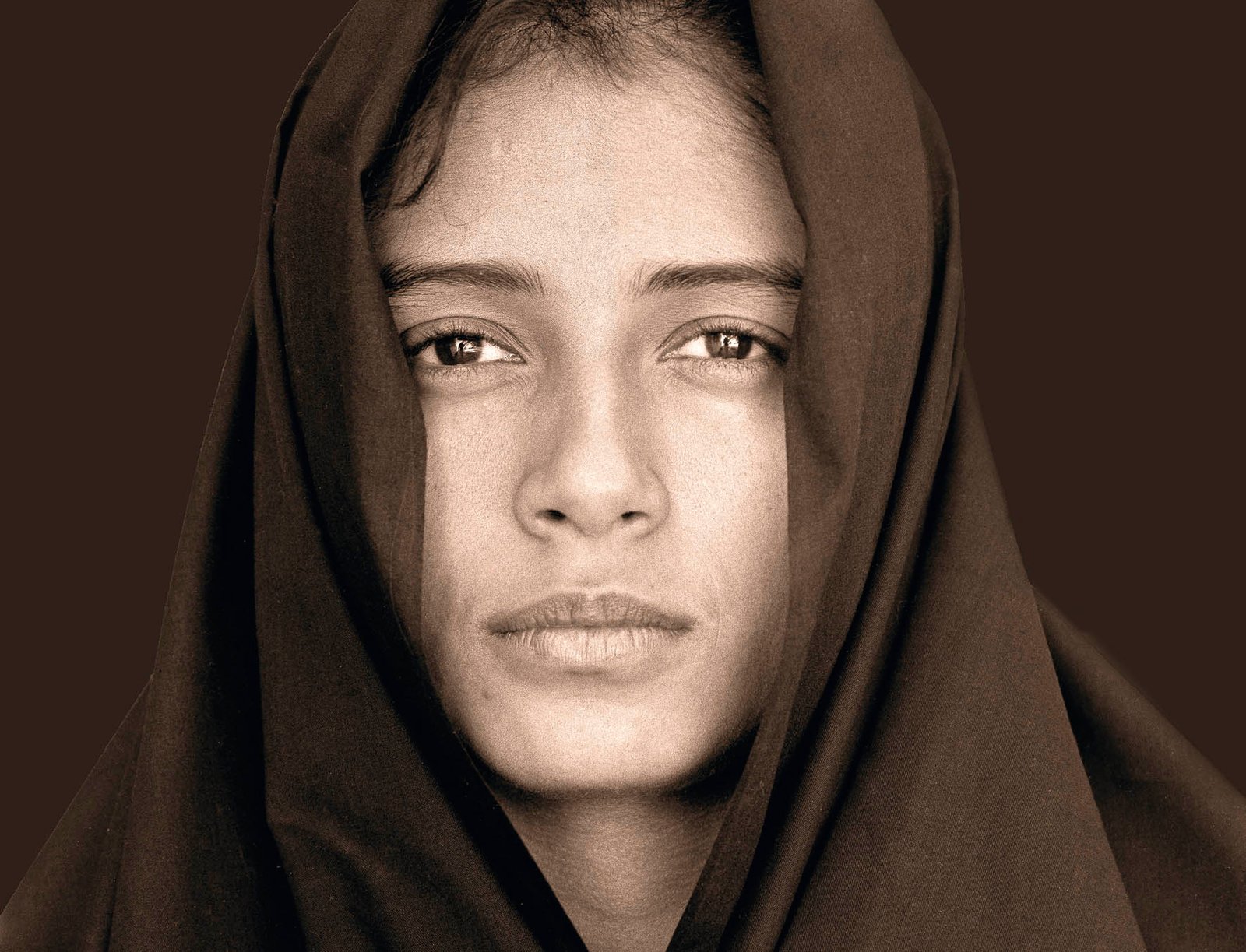

The figure in La Rosa (The Rose), an image created by the Guatemalan artist Luis González Palma at the end of the 80s, stares out at us through the disturbing white of her eyes. Haughty, she holds high a head crowned with petals and death. Neither happy nor sad. Not dark-skinned, but sepia. Her face serenely bears traces of the ruins of clashing worlds, violence, and uprooting. She is, however, alive. Perhaps she stares out at us as a reminder. Perhaps she is only beautiful so we will not forget her.

She remains rooted in the center of essential Latin American images from the past three decades, blooming simply inside the fluid mirror that González has been building to reflect ever-changing bodies. In a format that is not strictly photographic, documentary, or pictorial, his images emerge with their wounds and victories clearly on display. Surfaces of flesh through which history seeps.

One special image provides us with a key. In it, a young boy is just barely visible behind a large crucifix. Only a piece of the boy’s head containing his smooth, black hair and eyes can be seen; his mouth, however, is covered by the inscription INRI and his body by the lacerated body of Christ on the imposing cross. This was what happened literally during colonization, when Catholic images replaced indigenous ones. The Virgin Mary’s mantles of purity silenced the fertile convulsions of the Madre del Maíz (Mother of Corn); the martyrs’ wounds supplanted the spots on the Jaguar-Men; the Savior’s stigmata replaced the scales on the Plumed Serpent. Christ’s isolated, forlorn body swallowed the pagan connected to the natural world of the original inhabitants.

La Rosa.Photography and mixed technique. 50 x 50 cm.

La Rosa.Photography and mixed technique. 50 x 50 cm.

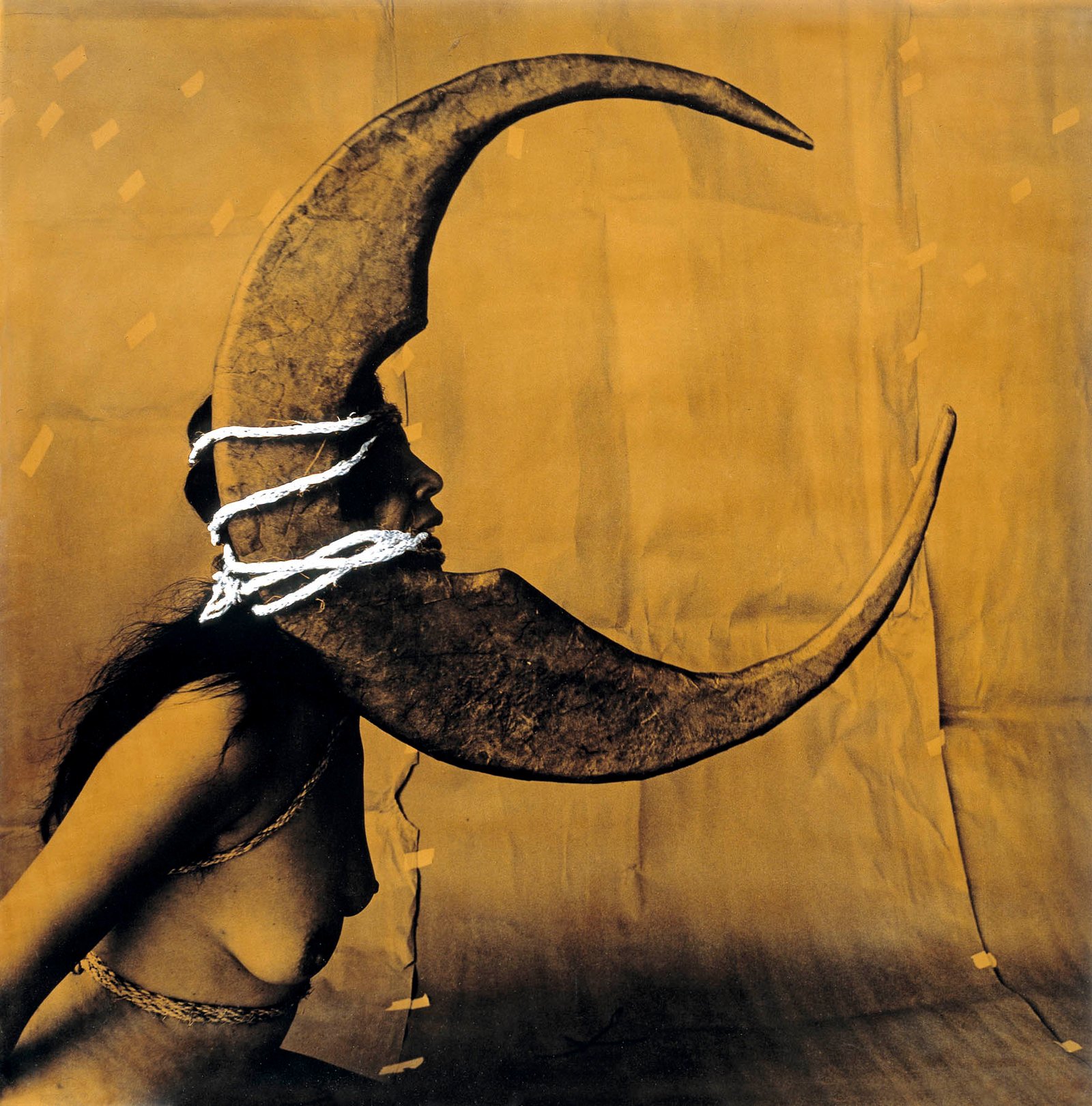

This violence in images persists and continues to be replicated every time an anthropologist’s camera or a tourist’s cell phone focuses from above on the mystery of mestizo bodies. They don’t see themselves reflected in images that devalue or exoticize them. And this was the problem that González faced when he began to look at the survivors of the Mayan cultures in his country. González understood that photography is fiction, that the human body is comprised of layers of history, and that memory is resistance. Renewed mythologies then began to emerge from his laboratory to counterbalance the stereotypes: the fierce Moon Woman, a crowned and thick-lipped America, legions of jungle-winged angels.

To capture these densities and complexities, his portraits had to break the flat surface of photographic prints. They exploded out of the walls and replicated the strategies used on religious altars. Fearlessly, shamelessly, he accumulated, mixed, and assembled crowns of thorns, dry branches, and nails, emulating to a certain extent Catholic icons, while exercising total freedom to incorporate pagan objects such as feathers, rocks and oils. European Baroque gold retains the traces of the indigenous hands that extracted it. The red of royalty evokes that of the blood shed. The fabrics reproduce modern shrouds and the sweep of the bullfighter’s cape.

La Luna.Photography and mixed technique. 50 x 50 cm.

La Luna.Photography and mixed technique. 50 x 50 cm.

More than certainties, González raises questions in his enigmatic compositions, seeking out the gaps in standard narratives, the narrative silences, the darkness that pushes out aesthetics and beings. His exhibitions, therefore, take place in half-lit shadows, like those in temples. What has art shown and what has it hidden? Who has had the right to an image and who has not? Who decided what is beautiful and what is ugly? What is civilized and what is barbaric? What we are and what we are not?

The body appears fragmented in his works, unfinished. Eyes sink into the folds in the paper, part of a nose doesn’t match, one face mixes with another, mouths nestle between eyelids, arms are freed from bodies and become lost, and hands grope the void. Or, the body simply disappears, leaving behind only a trail: a human-shaped piece of cloth, solitary beds pierced by a wall, dining rooms where no one ever came to dine.

Free of drama or tragedy, with no pamphlets or speeches, no shouting or complaining, the artist silently observes. He rummages, trims, reorders, decorates, assembles, covers the photos with Syrian asphalt to drench them in time, renders the eyes whiter and more powerful, and adds ancestral symbols or syringes, or contemporary geometric lines, assisting in this way with the daily genesis of the Latin American body, in its daily missteps and resurrections. Miscegenation has not only been submission, but also resistance, weaving, and reconstruction, and González’s imperfect, melancholy, intriguing images are part of it.

La Luna.Photography and mixed technique. 50 x 50 cm.

La Luna.Photography and mixed technique. 50 x 50 cm. Sin título (Serie Möbius). Print on canvas and gold laminate. 30 x 30 cm.

Sin título (Serie Möbius). Print on canvas and gold laminate. 30 x 30 cm.