By: Iván Beltrán Castillo

Photos: Lisa Palomino, David Gallego, Sergio Rodríguez

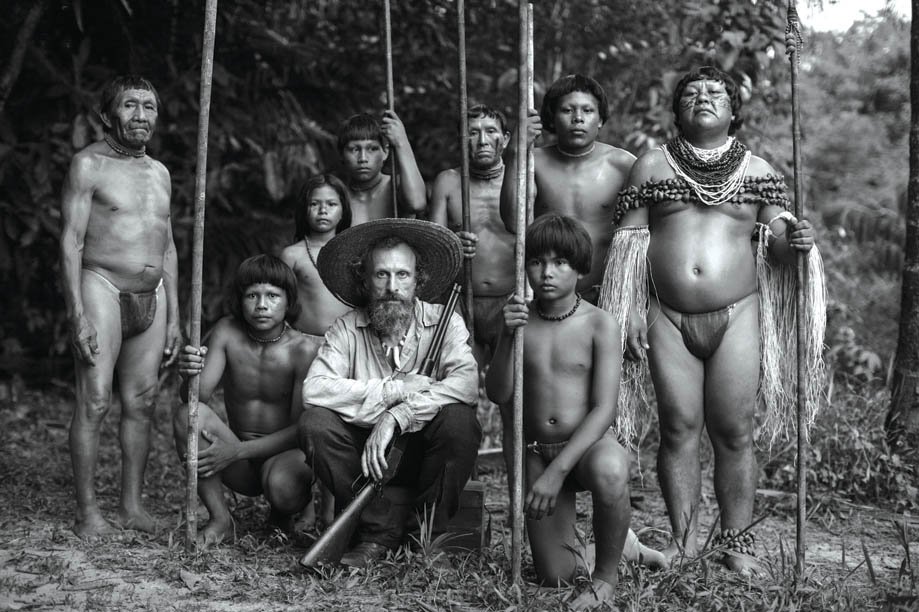

During the frenetic days of the film festival, when the streets of Cannes are thronged with all kinds of people, including some rather eccentric, “literary” or strange characters, one of the most recognized and besieged teams was that of the Colombian film Embrace of the Serpent, from the filmmaker Ciro Guerra. Enraptured by images that make the movie an inner voyage and a rite of passage, French, U.S., and Swedish audience members clamored to take photos with the unusual troupe.

It seems that after the inaugural showing, those inhabitants of the rational world, those descendants of Voltaire and Descartes and admirers of progress, were unable to stop reflecting, whether cheerfully or circumspectly, on what they had seen, perhaps mirroring the members of the indigenous tribes of Latin America on the other side of the world in their astonishment and bewilderment at the coming of “civilization.” Some people cried, others simply swore they would someday visit Amazonia; most felt inklings of a new awareness. Everyone applauded the movie in a feverish standing ovation that lasted more than fifteen minutes. They agreed that the film deserved the award given during the “Directors’ Fortnight,” an independent session parallel to the official festival, but one that over the years has become more significant and definitive than the festival itself.

Ciro’s adventure began a long time ago, and could undoubtedly be the genesis of another film or a great book. A native of Río de Oro in the Colombian department of Cesar, he studied cinematography at the National University of Bogotá, quickly turning his life into a reflexive and dynamic dialogue with the cinema.

One after another, ideas that come to him have always been carefully recorded, as have memories and images that perturb his imagination, providing grist for the mill of future films. But he claims that one of his first and most persistent obsessions was to film in the heart of the Amazon region. That desire took root when he was just a child looking at a map of Colombia and noticing the enormous size of that untamed department, which covers more than 25% of the country’s territory, like a sorcerer who dazzles amidst boring and commonplace people.

His appointment with greatness would be somewhat delayed. He made two feature-length films that gave him name recognition and credibility —Shadow of the Wanderer and Wind Journeys— but waited until he became one of the few filmmakers to make a living from the movies to take on the jungle adventure that was feted in Cannes.

“Now I remember everything: my dream of reconstructing the memory of a lost time; my young passion for the jungle; my efforts to turn it into a tangible experience; my years of work with fourteen script rewrites; the serious perils of remaining too long in the Amazon; reading the books of explorer Theodor Koch-Grünberg and botanist Richard Evans Schultes, whose contributions helped change my vision of such a vast cosmos; the secret, sacred plants; and the people who have tried, perhaps in vain, to bequeath to us a coded message from that world. And more: the inner struggle between rational arrogance and the flowering of sensitivity and fear, sadness and awe at narrating a virtually destroyed world,” said Ciro Guerra, in an attempt to synthesize this radical experience.

The film now appears to have taken on a life independent of its creator. It premiered in Colombia to large audiences and praise from critics, actors, and filmmakers, but was an often painful life experience. It is the story of the sometimes implausible encounter between two European explorers —one in the early 20th century and the other in the 1950s— who made contact with the original peoples of Amazonia, understanding them, respecting them, and valuing their store of knowledge. Ciro considers those two men important trail-blazers. They were the first Westerners to not see the indigenous peoples as slaves or possessions. They are the fathers of future psychedelia, humanism, and an unprecedented understanding of the universe.

Ciro Guerra confirms that the jungle is not an easy place, nor does it surrender its secrets to those who do not understand or respect it. Filmed in Vaupés, far from the tame tourist jungle of Leticia, the undertaking was also an exile. The filming team was captive for seven weeks, experiencing the daily risks implicit in such a project. Survival conditions have not changed much with the passage of time, and even now travelers are plagued by illness, silence, ancient voices nestled in every tree and landscape, madness, and death.

Ciro Guerra noted that “It was never my intention to sum up, or much less explain, the Amazon. That would be an absurd ambition. Nor did I want to make a documentary.”

“The film is essentially fiction and curiously, only one of its chapters, the one telling the story of a delusional Brazilian messiah who inspired a strange fervor among his followers, is true. It is not a linear narrative. In these surprising lands, history is circular rather than linear.”

“Cycles repeat, existence acquires a fantastic circularity and facts are like lines in a long poem, in which the senses and the perpetual voyage seem to be the most useful keys. Oddly, jungle time and the inhabitants’ conception of it resembles quantum physics.”

The actors in Embrace of the Serpent threw themselves into the project with an attitude akin to religious belief. The cast included professional actors —like German actor Jan Bijvoet and U.S. actor Brionne Davis, who played the explorers— and some who had never seen a camera or a light, like Antonio Bolívar and Nilbio Torres, who shared the role of the main character Karamakate, whose journey continues from youth through old age.

A Film for Remembrance

When his mother died, he felt like the world had ended, that a rift had opened in the universe, and that all the meaning of reality had begun to dissolve; the loss of filial, loving, and sublime feelings sent him into exile.

These memories, which are part of his innermost core, caused filmmaker César Acevedo to fall prey to a passion for cinema. Perhaps he discovered, like so many directors and scriptwriters, that more than a distinctive trade or an exciting profession, movies could be a path to understanding and a way of exploring beyond conventions.

After studying journalism at the Universidad del Valle and specializing in cinematography, the Cali-born filmmaker devoted himself completely to film. He had a film-club in Cali, joined research and script-writing groups, and was an assistant director for iconic films like La sirga (The Towrope), Los hongos (Mushrooms), and El vuelco del cangrejo (Crab Trap).

Barely a week ago, his film Land and Shade garnered three awards at Cannes: the Golden Camera for best debut work, the Critics’ Week Visionary Award, and the Audience Award. He did not expect such recognition, and he believes it is due to the fact that he filmed an honest story, deeply rooted in the earth of Colombia, but at the same time, like a turn of the screw, one that is also an intimate poem and a inquiry into the most universal human feelings of love, oblivion, loneliness, and abandonment.

“The film tells the story of a Cauca Valley farmer named Alfonso, who is forced to return home to care for his ill son. After returning, Alfonso realizes that the world he knew has disappeared and he engages in a fierce struggle to repair broken relationships and stem the tide of forgetfulness. All of this takes place in the world of sugar cane cutters, where injustice, exploitation and a total lack of respect for human rights have always been the norm,” said César as he emotionally recalled the recent awards ceremony attended by his father, a key figure in his life journey.

César Acevedo laments that bureaucratic difficulties continue to plague film directors in modern Colombia. He speaks of the involuntary exile that sends nearly all of them to Bogotá if they hope to crystallize their cinematic dreams. He says that there are no opportunities in his native Cali, since it is in the thrall of a cultural bureaucracy that “allots all the resources to dance, in an irresponsible folk-tinged waste.”

The Decidedly Emphatic Charm of Latin American Cinema

Once negligible, the impact of Latin American cinema at the Cannes Film Festival has increased significantly. Year after year, the jury, the critics, and the audiences pay more attention to forceful, exceptional, sometimes violent, stories from this side of the world. In addition to the two Colombian films, the recent festival featured:

• The Mexican film The Chosen Ones, by director David Pablos. This film is a raw portrait of trafficking in women and prostitution in the confused and sordid México of today. Pablos was the only director who received a special nomination in the official competition.

• Beyond My Grandfather Allende, a film by Marcia Tambutti, granddaughter of the Chilean President overthrown by bloodthirsty dictator Augusto Pinochet, that focuses on the personality, achievements, mistakes, and frailty of her grandfather, who is an iconic figure in Latin America.

• The award for best script went to Mexican director Michel Franco for a cryptic French film titled Chronic, likewise directed and produced by Franco. It is the story of an odd, peripatetic nurse who works with terminally ill patients.