The Colors of Cruz-Diez

By: Ana Teresa Benjamín

Photos: Carlos E. Gómez

Ninety-one years have left their mark on the face of Carlos Cruz-Diez, but his salt-and-pepper hair falls rebelliously across his brow like a teenager’s. A few weeks ago, during a talk to a hundred or so architecture students who gathered to hear him at the Convention Center in Panama’s Ciudad del Saber, this lion of kinetic art reiterated that an artist does not decorate spaces: “He is a conceptualizer who helps to find solutions for cities,” he stressed.

Sunk in a chair on the Center’s dark stage, Cruz-Diez hardly cuts an imposing figure. However, his works certainly do, as they flash onto several screens arranged around the room. For example, in Rey Juan Carlos I Park in Madrid we see a physiochromie that has surprised more than one passerby with its apparently imminent collapse; the chromatic induction used to design the seats of the concert hall of the National Youth and Children’s Orchestras in Venezuela, filling the space with color; the chromatic ambientation devised for the control room of a hydroelectric plant —also in Venezuela— converting a work space into an art experience; and Cromovela, calling to mind a tornado on Panama City’s Coastal Beltway.

Venezuelan native Cruz-Diez (born in 1923) confessed in an interview that he was always a poor student: “I spent my time making little figures.” He entered the Caracas School of Fine Arts in 1940 and soon afterward, he was capturing the poverty of his country in paintings. “I thought a painter should report an era. I thought I could change the situation by depicting poverty,” he says several decades later, seated at the computer in his Articruz Workshop in the Panama City neighborhood of Pedregal.

“But then I sold those paintings of poverty for a good amount of money and I felt like an idiot,” he declares. He smiles slightly, shrugs his shoulders ironically, glances at the screen, and clicks. Cruz-Diez is on good terms with the Illustrator. He returns.

Before immersing himself completely in art, Cruz-Diez worked as a creative director at an advertising agency, as a newspaper illustrator, as a graphic designer, and even as a photographer. “To finance my artistic endeavors, I became a graphic designer and did a lot of photography. Photos were part of a survival and experimentation mechanism,” he told BBC World, speaking about an exhibit of his black and white photos at the Caracas BBVA Provincial Foundation in July 2013.

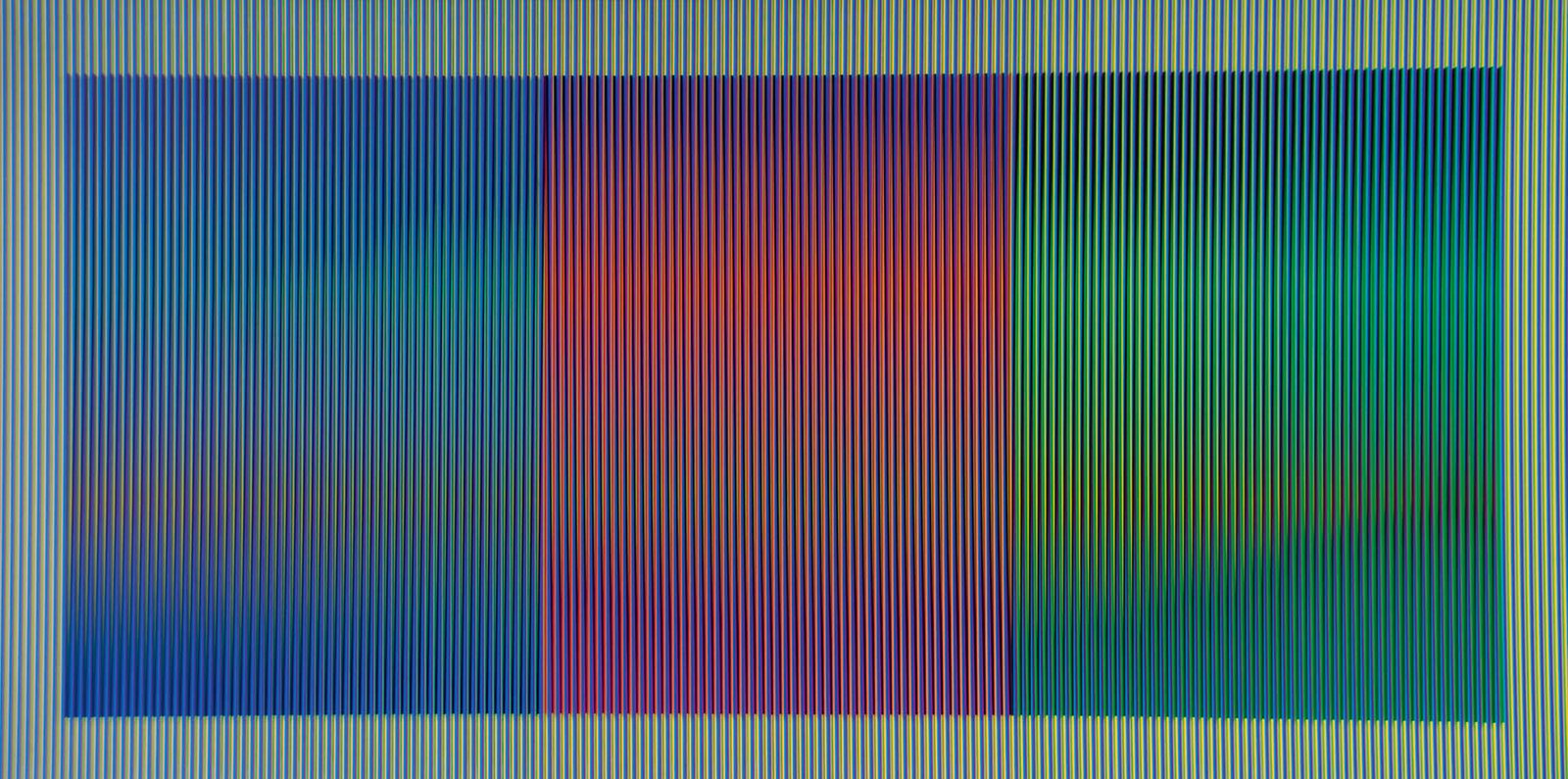

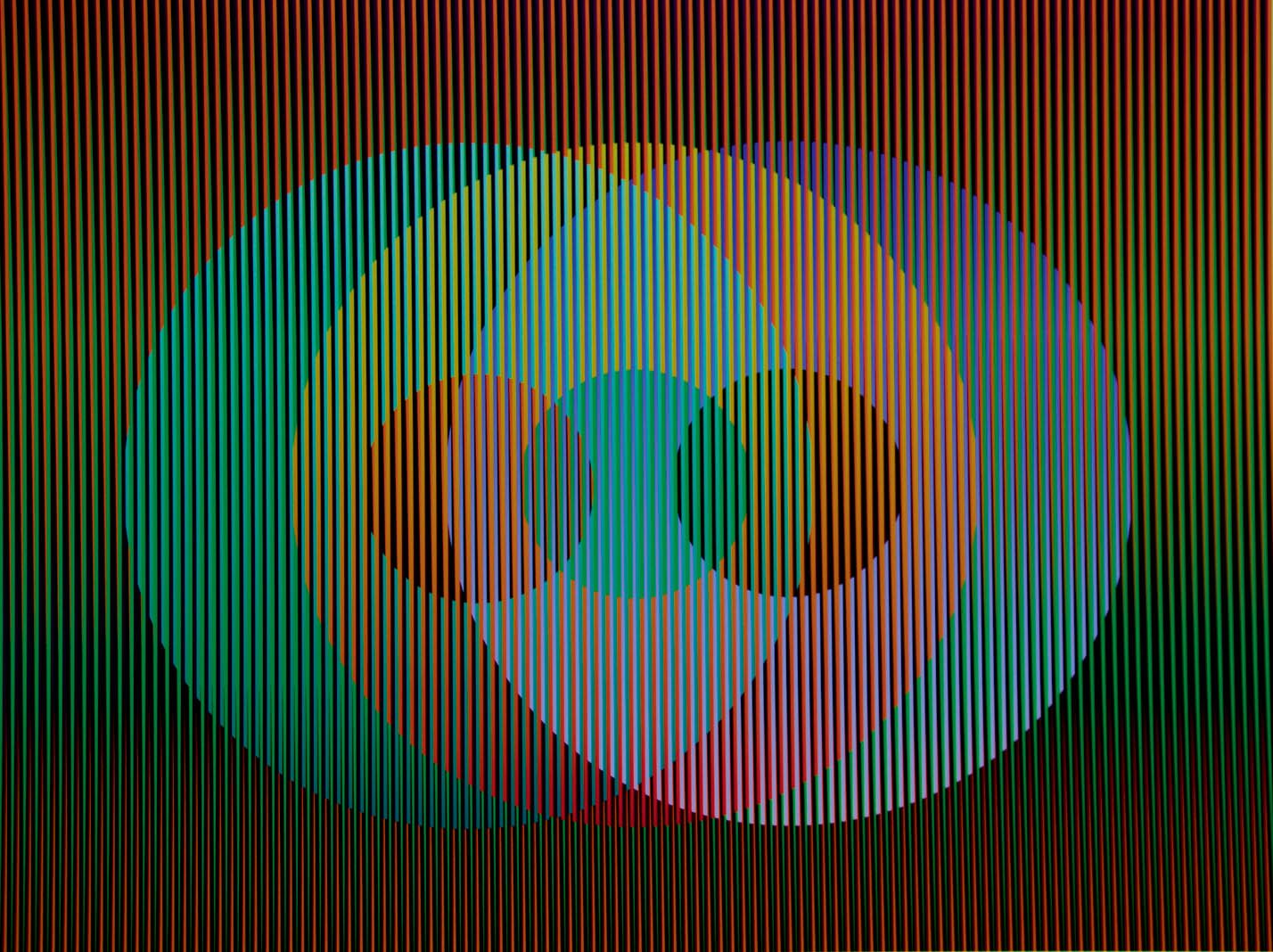

As he worked several jobs to survive, the artist sought ways to innovate. He began investigating how color had been used in different eras and how people reacted to it; he also looked at color as an independent entity, not as a component of shape. He found his voice. “Color does not just add color. The space we inhabit is always full of color, and color can change when nuances and subtleties appear.”

In his book, Reflections on Color, the artist reflects, “I learned that color is an important way to sharpen the perception of ‘reality.’ Today’s ‘reality’ is not the same as that of the 12th century, when life was merely a springboard to eternity. We, on the other hand, believe in the ephemeral; everything changes and is transformed in an instant.” This is how color went from playing a cameo role to being the star of the momentary, of the ephemeral, of perception, and of personal experience.

This was just the beginning. Since Cruz-Diez needed to share his voice, he started searching for a better platform “for showing how colors coalesce and dissolve.”

The Articruz Workshop is comprised of several galleries, which in turn form part of an office complex located in an outlying area of Panama City characterized by factories, industrial installations, shabbiness, and heavy traffic. The cement jungle prevails.

But the doors of the Workshop open onto color: the eye alights first on furniture in steel combined with red, black, and lime green, and then on the striking ornaments that often adorn the desks of creative individuals. A further door leads to the work area, which contradicts any preconceived idea of an artist’s studio: no mess, no smocks, no paint pots. Everything gleams immaculately white, more like a laboratory. Here stand two enormous Mimaki printers, there the laminators that give color to the PVC strips Cruz-Diez uses for his works. On one side is a machine that bends aluminum, on the other, a paint lab that blends all the colors the artist invents on the computer. There are lasers, pliers, drills, and screwdrivers, and a paint booth inside which a worker seals one of the Venezuelan artist’s creations with a special substance.

Cruz-Diez has had a workshop in Paris since the 1960s. He headed for Paris after failing to find acceptance in his native Venezuela. “Paris was a stage where we could discuss ideas,” he explains. In 1973, he opened his second workshop, this time in Venezuela, where it remained until 2009, when he decided to move it to Panama for family and strategic reasons.

He has spent his long career creating works for “the cathedrals of today” —banks, public spaces, companies, schools, etc. In July 2014, he heard that one of his sculptures, located at the entrance of a French school and valued at some 270,000 dollars, had been destroyed “by mistake.” It was scrapped because it supposedly looked like it was about to fall over. Cruz-Diez commented that he would never have imagined that “such an incident could occur in a country that considers itself a fervent partisan of the arts.”

In November of that same year, fashion designer Oscar Carvallo presented his collection Kinetic Voyage II, which consisted of twenty dresses with prints, textures, styles, and details created from some of the works of this op artist.

Admired and respected for his work and his research, this slightly-built man says, frankly but humbly: “I think I have been saying the same thing for fifty years: color is a vital experience, and my art is discovery, revelation, working in continuous transformation.” In an earlier interview, trying to describe what he does, he called it “participatory, manipulable” art. More than one person looked askance at this. Nowadays, young people understand him immediately: “They tell me it’s interactive,” he says with a smile and another shrug. He excitedly demonstrates how he creates those “illusions” on the computer until he gets what he wants. “My work is completely planned, systematic, and mathematical,” he explains. And then he turns back to his work again.