We Brought the Ocean

By: Uriel Quesada

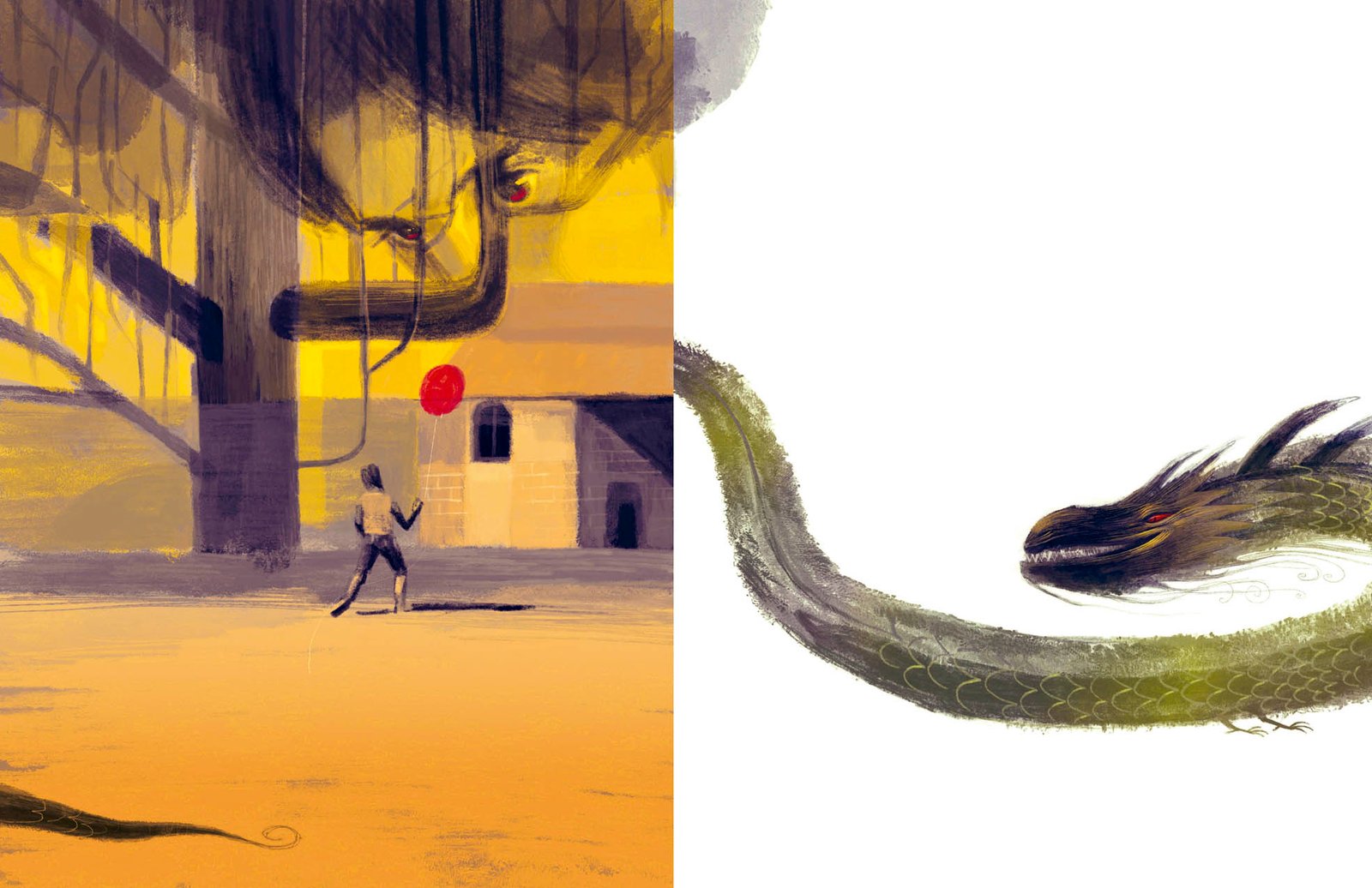

Illustrated by: Henry González

Selection and Compilation: Carolina Fonseca

I haven’t seen the ocean for ten years. My intense desire to see it this morning made me beg my mother until she cried. I remember the ocean very well despite the passage of time and how young I was. I can almost feel the rhythmic movements, the sound of water seemingly gnawing at the sand, and the boats in the distance rising and falling on the waves.

I was six then, the first time I saw the ocean. Dad never kept his promise to take us back another summer and then came the pains, the headaches, the October day when I couldn’t stand up, followed by boring years in bed spent dreaming up and believing in promises that never materialized, just like that promise to go back to the beach. I recall the most significant promises one by one: my health restored, a teacher to help me finish my schooling, a wheelchair so I could get out of the house, a couch so I wouldn’t have to lie in bed all the time, books with big pictures, a portable radio. They will soon offer to bring a priest so I can make my peace with God, but I know they won’t actually do it. What harm could someone like me, an innocent prisoner who cannot escape a threadbare room, who has spent so much time out of the world, do to anyone?

But I shouldn’t be ungrateful. Already poor to start with, they have sacrificed further to make my illness bearable. Since they didn’t trust the Social Security system, they paid for a couple of appointments with a private neurologist, hoping to be told that the diagnosis was wrong. I heard the doctor say that the only thing to do was to wait and ask God for a miracle. I was relieved when the doctor said he would not be back, since that meant they would not have to admit they could not pay for more treatment.

They also splurged on things I had no use for: dark glasses, a basketball, a couple of cans of peaches, and nougat imported from Spain. In return, I accepted a Bible from them. I allowed them to take me to Easter Week observances and to make a promise to the Virgin. The saints have proven to be deaf, as has God. My family grew even poorer and everyone made do without many things in order to ease my drawn-out death.

Sofi and Lalo got jobs; Cuyo wants to drop out of school to follow in their footsteps. Dad drinks a lot more now and I have heard him say that it’s because of me. Mom doesn’t need to cry as much as before. Her eyes are sunken and even her smiles reveal bitter impatience and resignation, which might be the only thing God has granted us.

I don’t read the Bible any more, not even the parts about Lazarus, or the blind man, or the demoniac. I just want to die. I know I’m going to die; they haven’t told me so, but I know it. You can feel it in the house, see it in their faces, and hear it in their whispers. After so many years of suffering, I’m used to the pain. I don’t need pills or tinctures and I haven’t taken them for months; I dispose of the medicines through the cracks in the floor so that others think I’m doing what I’m supposed to do. I’m not fooling myself, I just want to die. I smile, I don’t complain, I oblige them with devout zeal, but there is no hope for me. The only thing I’m sure of is that I will die and I want to go soon, today, this minute.

As a last wish, I would love to see the ocean. That desire, that impossible wish, wormed its way into me as I slept, taunting me, since anyone except me can get to the ocean in just two hours. It’s a compulsion to break down one of the walls of this moment. I begged Mom to take me, until we both ended up in tears. But how could I reach the ocean? Who would venture to take a dying young man to the beach? Considering that it took a month to buy me those peaches and that Cuyo had to do without a blanket he really needed, where would they find the money to take me?

Mom cried through to noon. She had not cleaned the house or cooked lunch. Our aunt and uncle arrived with Dad and our cousins. I heard them talking on the other side of the wall before the adults came in to persuade me to ask for something else. Dad said it really wasn’t a question of money, but rather that I couldn’t bear such a difficult trip.

I persisted until I thought they gave way. They went to look for a car, and everyone chipped in some money. But when the torpor of one o’clock rolled around, you could tell we weren’t going anywhere. Before I dropped off to sleep, my little cousins came up and asked if I really wanted to see the ocean. Sleepily, I answered that it was what I wanted most.

I’m awake again. Mom is in the room. Her face is pale and there are purple circles around her eyes. She’s shaking.

I have lived long enough to hear my mother categorically say “no”: there is no car, no money, you can’t travel by train. No travel today, but perhaps tomorrow.

“What if tomorrow is too late?”

Mom went back to the living room to cry some more and the house is quiet because my aunt and uncle can’t stand the weeping.

“I want to see the ocean!” I cry again and again. “I want to see the ocean!”

Then my little cousins come back. One stands guard in the doorway, while another boy opens the window; he and the little girls drag the cot to where I can see the clear sky and the breeze from outside uncovers me.

Still others hold up and stretch a sheet so that it flaps, producing a rhythmic sound that all of us cousins recognize. I feel the salty taste of the water in my mouth as the children imitate seagulls and boat horns. The smallest of my cousins brings me a sea shell to hold in my hands and a conch to hold to my ear. Speaking for everyone, she says:

“We brought the ocean here. If you want to see it, all you have to do is close your eyes.”