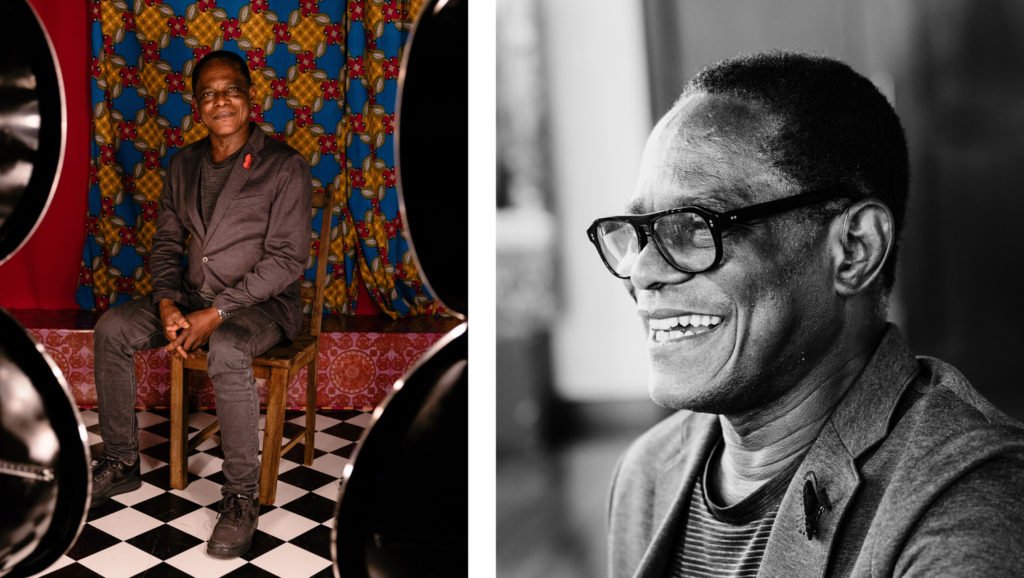

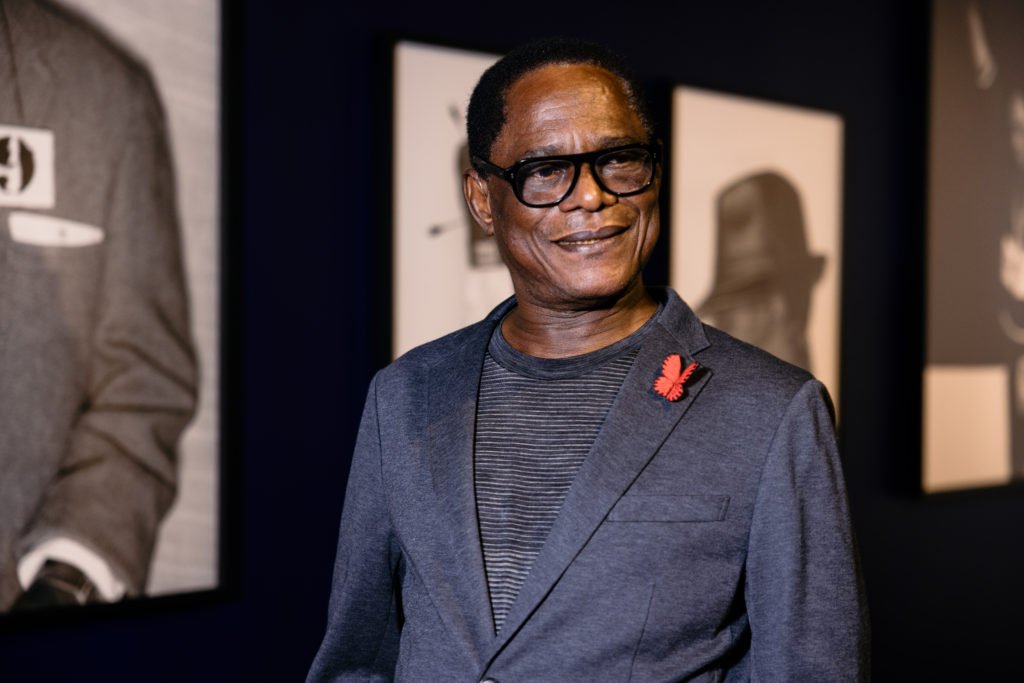

Samuel Fosso. Finding Oneself in the Other

By Alexa Carolina Chacón

Photos: Susana Aramburú

Samuel Fosso has spent his entire life in front of the lens. He is a photographer, not a model, but he has used his own image as a tool for activism and a canvas for expression by placing it where his colleagues are likely to put a different subject. In his work, which can now be enjoyed in Panama thanks to the heroic efforts of the Casa Santa Ana Foundation and the Panama Canal Museum, he brings historical figures to life. He uses their clothing and poses to teach through their images and, in some cases, to criticize. All of Fosso’s work shares the goal of making Blackness visible, giving it ownership of its own narrative. His subject is the Black experience and the who and how of its protagonists. Of all parts of Panama, Fosso was most impressed by Portobelo. He saw himself reflected in the history of the town and its people, and found himself again.

What has the “Finding Oneself in the Other” exhibition, held in Panama, meant to you?

My exhibitions to date in Latin America —there have been four— motivated me to understand and observe the Afro-American diaspora, and sadly, the mistreatment of Black people.

When did you start taking photos impersonating major historical figures? Did you ever imagine that the world would one day end up doing the same thing with cell phones?

I never imagined it! I started making these self-portraits in the 1970s, when I was very young. At that time, there were no mobile phones. And, of course, I had no idea what was on the way.

You visited Portobelo. What did you think of the cultural representations you saw there?

For me, the most impressive were undoubtedly the masks, because they’re the same masks that we use in initiation celebrations in Africa during a festival that takes place in October. But everything caught my eye: the bags [de la vestimenta congo], the history of the “cimarronaje,” or marronage…painting oneself to protect oneself from enemies (the enemies at that time were the white people). Also the tarts made from tapioca (cassava), which is a food I like a lot that is also widely used in Africa.

What might you say to Samuel Fosso the child, who felt he didn’t exist in society?

More than saying anything to myself, I would thank God, because when I started out at thirteen, I never thought my work would become this huge. I took photos for my family, and especially for my grandmother. During the war, between 1967 and 1970, my grandmother and I were separated by a great distance and photography allowed me to communicate with her. Hence the self-portraits. I also thought that I’d save the photos for my children so that I could show them what I was like when I was their age.

Your African Spirits series was created in 2008. How would you update that series today?

It was before Black Lives Matter, which, in a way, I feel like I anticipated. The series was born after the Biafra war, a civil war motivated by oil interests that left more than a million Black people dead. During this time, I looked at my children and I realized what slavery was. And I discovered that it was important, as an artist, to do something about the Black Spirit. Something that would recognize those who gave their lives to free us: those people who suffered and fought to defend the interests of Blacks –in America, in Africa, or here in Latin America– and who don’t show up in school books. I made African Spirits so that future generations will find those stories in museums.

What would you like Panorama readers to know about you that they don’t already know?

That they must not seek to know me. Let them seek to know history. Let them seek to know the reasons why, the history of African Spirits (and my other works), because I embody those characters in my photography.

Leave a Reply