Uprising of the Muses

Carmen Mondragón (1893-1978), Autorretrato como colegiala en París, 1928, Óleo sobre cartón, Oil on cardboard, 102 x 76 cm, México.

By: Sol Astrid Giraldo E.

Photos: Cortesía Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Chile

The invitation came from a palatial edifice in the south. Even though they had to cross mountain ranges and oceans and travel across time periods and out of obscurity, they made it. One by one, they climbed out of the discreet packing boxes and ascended the monumental staircases. This was a reunion of a kind that has never taken place in this century, let alone the preceding one. They could not possibly miss it. So, this is how these flowing-haired, open-minded centenarian ladies ended up here. Some had met before in cafés, academies, or galleries in Paris, Mexico City, or Buenos Aires at the dawn of the 20th century. Others had not traveled much beyond their native lands and had never dared explore below the equator. Even though they shared a certain feeling of family, they were never before gathered under the same roof.

The packing cases from nine countries (Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, México, Colombia, Perú, Cuba, United Kingdom, and Spain) were opened and the canvases set out to breathe before being united with those contributed by the Chilean hosts. The National Museum of Fine Arts in Santiago went into full celebration mode. Nahui Olin half-closed her mesmerizing eyes. Legless Raquel Forner strolled about with a head under her arm. Rosa Rolanda released butterflies. Remedios Varo wound her clocks in a new vision of time. Amelia Peláez fluttered a fan before her featureless face. Leonora Carrington’s exuberant one-eyed monsters walked on tiptoe, while Dora Puelma dragged a weightless doll and Frida Kahlo carried her sewing kit and letters.

Judith Alpi (1893-1983), Kimono blanco, Óleo sobre tela, Oil on canvas, 198 x 150 cm. Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Santiago, Chile.

Judith Alpi (1893-1983), Kimono blanco, Óleo sobre tela, Oil on canvas, 198 x 150 cm. Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Santiago, Chile.

The time had come to show off their best outfits: Judith Alpi slipped into a sophisticated white kimono; the daughters of Anita Malfatti and Petrona Viera sported African turbans; Lola Cueto wrapped herself in a Oaxacan shawl; and Helena Izcué and Julia Codesido flapped colorful Aymará blankets. Others, like the defiant Maruja Mallo, took off their hats… and everything else. Sinewy Laura Rodig challenged the walls with her ambiguous frontal nudity and sweet Elmina Moisán was naked in the bath. The heavy breast hanging over the arm of statuesque black woman Tarsila do Amaral defied the laws of anatomy and morality, but calmly greeted Débora Arango’s brash pubis.

Indeed. These ladies had arrived for an appointment to see themselves and each other without male intermediaries or the protocols of an art world that had traditionally excluded them. Joyful, free, old, black, child-like, indigenous, flirtatious, fat, skeletal, broken, exuberant. No aides needed.

Izquierda: Débora Arango (1907-2005), Anselma, 1940, Pintura al óleo sobre cartón, Oil paint on cardboard. 37 x 24,5 cm. Coleccción de Arte SURA (Medellín). Derecha: María Dolores Velázquez Rivas (1897-1978). India oaxaqueña, 1928. Tapiz bordado, Embroidered tapestry. 118 x 74 cm, México.

Izquierda: Débora Arango (1907-2005), Anselma, 1940, Pintura al óleo sobre cartón, Oil paint on cardboard. 37 x 24,5 cm. Coleccción de Arte SURA (Medellín). Derecha: María Dolores Velázquez Rivas (1897-1978). India oaxaqueña, 1928. Tapiz bordado, Embroidered tapestry. 118 x 74 cm, México.

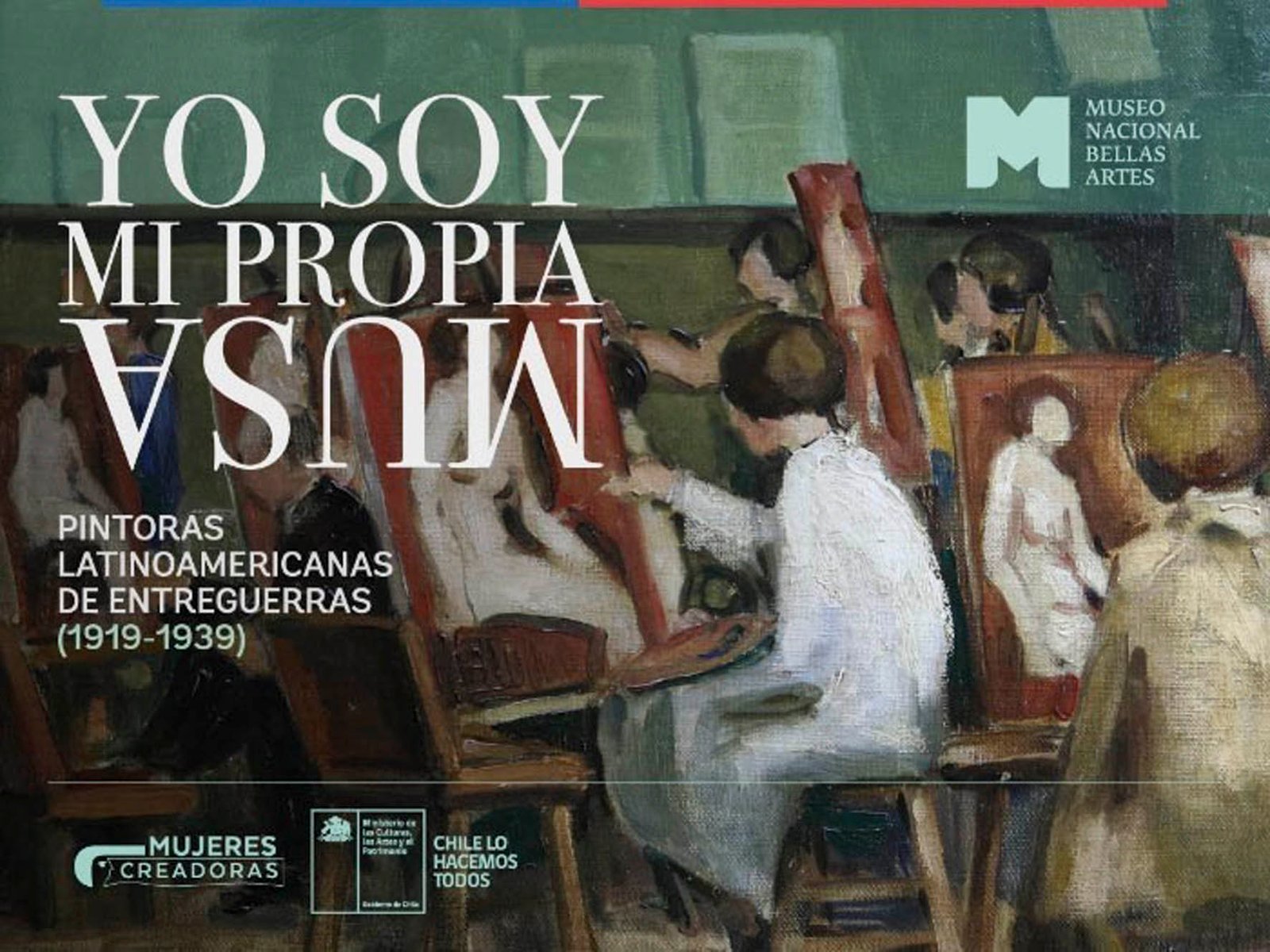

This was the birth of a reunion that was undoubtedly one for the history books. Gloria Cortés Aliaga, curator of the Chilean National Museum of Fine Arts (MNBA) and indefatigable researcher of Latin American art by women, was in charge of staging the exhibit “I Am My Own Muse. Latin American Painters of the Inter-war Years (1919-1939).” By bringing together these artists, who are generally seen separately, she weaves a complex narrative that makes it possible to understand the artists as members of an active, free-wheeling, rebellious, and political community. A collective formed by women who, in addition to their public struggles for freedom, faced daily struggles for freedom at home. Although these women were not yet citizens with the right to vote, they created a space for their voices, and above all, their perceptions. Their presence caused the visual structure, based on privileges of male power, to teeter a bit.

This new perspective allows us to see the birth of a previously unseen Latin American female body that bears witness to the realities of gender, culture, and race. This is an epic, sometimes muted and sometimes raucous, that unfolds in environments that are more propitious, like México, and others that are definitely more hostile, like Colombia, with its cosmopolitan and provincial figures. These women shared the stage with avant-garde male artists who sometimes supported them, sometimes ignored them, and were sometimes markedly hostile. In any case, the latest research reveals differing perspectives and issues that will be key to understanding this disquieting community that is finally shaking off the dust of oblivion.

Ana Cortés (1895-1998). La Grande Chaumière, 1926. Óleo sobre tela, Oil on canvas. 32 x 40 cm. Colección Bernardita Mandiola.

Ana Cortés (1895-1998). La Grande Chaumière, 1926. Óleo sobre tela, Oil on canvas. 32 x 40 cm. Colección Bernardita Mandiola.