Fray Bentos Industrial Complex: A New World Heritage Site

Text and photos: Gloria Algorta

Timeworn cranes hover near the buildings of the former Frigorífico Anglo in Fray Bentos —now a World Heritage Site— seemingly floating on the dock rails. After surviving wars and famines, the cranes no longer fill the expectant maws of ships with Uruguay’s main exports: meat and meat products. The Uruguay River, which both divides and unites two nations, laps at the pilings supporting the cranes. The Argentinean province of Entre Ríos lies on the other side of the river, barely a stone’s throw away. The sun peeps out from gray clouds that have been busily dumping rain.

The city of Fray Bentos, capital of the department of Río Negro, lies some 186 miles from both Montevideo and Buenos Aires. A quick glance at the surnames in the phone book reveals the melting pot of immigrants who came here to make a living.

Around 1863, when Fray Bentos was still just a village called Villa Independencia, German engineer Georg Giebert began to manufacture a product created by scientist Justus von Liebig, a product that forever transformed the food industry: meat extract. Soldiers who fought in the Franco-Prussian war consumed that foodstuff produced in Uruguay, as had U.S. soldiers during the Civil War. The new plant was built in 1870 and the workers’ residential area grew along with it. Some 50,000 heads of cattle were processed every year.

As Liebig expanded his facilities, product range, and work force in the last quarter of the 19th century, the period also saw the construction of what is today known as Barrio Anglo, where the processing plant’s workers, employees, and directors resided in a kind of company town. Even though the houses were built by German workers, they are British in style. If you let yourself drift back in time, you will find yourself in an English working-class neighborhood, complete with discernible differences among the various categories of worker. Unfortunately for me, the Casa Grande (Big House) was closed, so I could only imagine the five o’clock tea served to the director and his family.

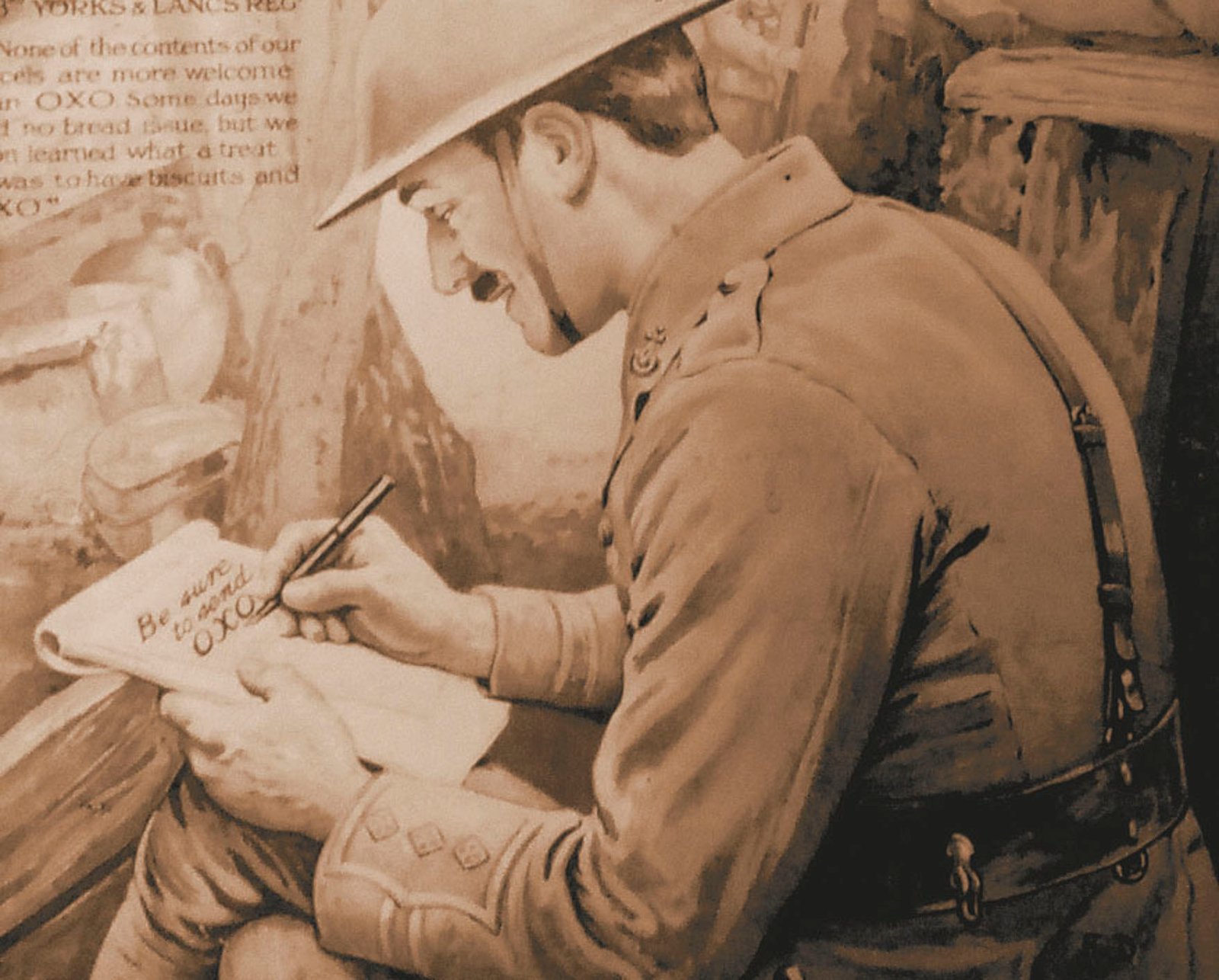

Liebig’s Extract of Meat Company Limited fell on hard times owing in part to conditions imposed on Germany by the victors in the Great War, leading the company to become Frigorífico Anglo in 1924 and eventually end up in the hands of an English consortium. When World War II broke out, demand for food grew exponentially, with corned beef, a concentrated protein packed in a specially-designed can, finding its way into the backpacks of many soldiers.

Production did not stop there: beef by-products, such as bones, skin, and even hooves were used to make other items. Local inhabitants often say that “The only part of the cow not used was the ‘moo’.” My kind guide, Miguel García of the Río Negro Office of Tourism and Culture, like all Fray Bentos natives, knows that the meat processing plant produced and exported two iconic products: beef extract and corned beef, which made Uruguay famous in Europe.

My museum visit taught me that Fray Bentos quickly became a brand, attracting many Europeans to this “exotic” country that produced such good meat. Great Britain was the largest consumer of corned beef and Oxo, a meat extract sold in soluble cubes; a Fray Bentos line of foods is still produced there.

Historian Boretto Ovalle, former director of the Museum of the Industrial Revolution —situated inside the old processing plant— notes that an English tank was dubbed “Fray Bentos” by its crew during the battle of Ypres. It is likely that this unusual name for a British tank arose from the crew’s feeling that they were “corned beef stuffed into a tin” when they were trapped in the tank for days on end.

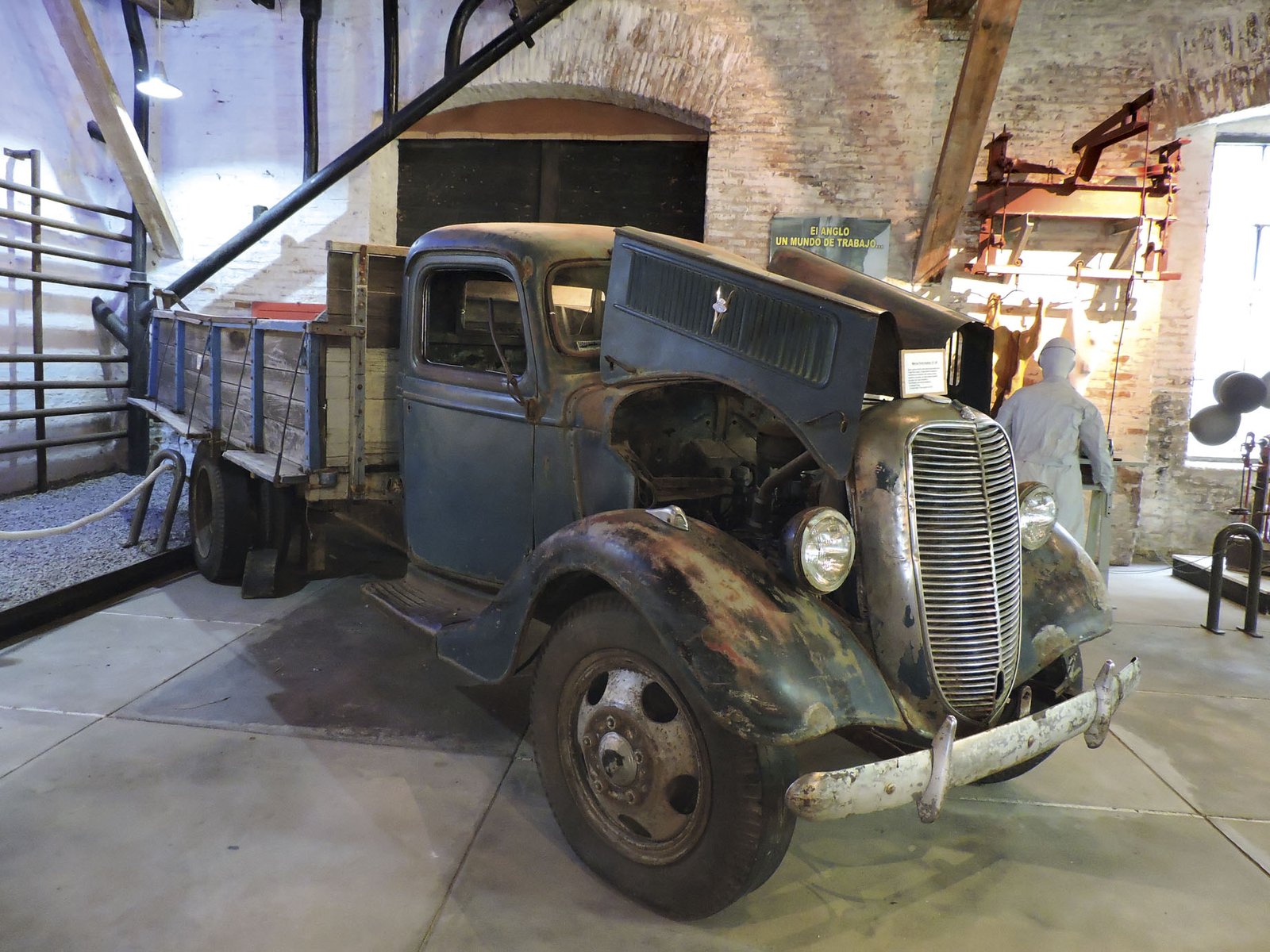

Time seemed to stop as I toured the plant’s central offices with Miguel. It seemed like the employees had simply stepped out for a moment. Forms and oversized account books still spread across the desks, the telephone switchboard has plugs in the jacks, and a huge teletype machine awaits its operator. There are also instructions for the most effective way to kill cattle. Only one desk seems to have been moved from its original position: that of a hefty specimen of a man who left the marks of his restless feet on the wooden floor. If these walls could talk, what stories they could tell.

The machinery, tools, and clothing of workers from around the world are on display in the museum. The first electric light switched on in Uruguay, in August 1887, is prominently displayed. Fray Bentos painter Ricardo Díaz Cichero adorned one of the room’s vast walls with a sweeping mural that depicts various chapters in the story of the meat processing plant: its founding, its glory days, and its decline.

The Frigorífico Anglo spurred development along the Río de la Plata, and the plant employed 4,000 people during its heyday. This was a substantial number, considering that the population of Fray Bentos was less than 25,000 in 2011. The plant’s imported technology was always cutting edge. Hulking mechanical, steam, and electrical machines now rub elbows in the same dark room, creating a fascinating display, even for someone like me who knows little about machinery.

Meat production has always been part of the history of Uruguay. A wartime clash, remembered as the Battle of Río de la Plata, was sparked by a Nazi attempt to cut off supplies to Allied troops with the German submarine Graf Spee, which was forced to seek shelter in the port of Montevideo for a few hours as it was besieged by British ships. To keep the submarine from falling into enemy hands, it was sunk by its captain in full view of astonished Montevideo residents.

A drop in demand for meat products signaled the onset of the first economic and political crisis of the 20th century. The crisis did not spare Frigorífico Anglo and it was nationalized in 1968; the plant continued to operate until 1979. Its final tumultuous era was marked by labor struggles and mass protest convoys and marches to Montevideo. The son of some Anglo workers told me that, at the age of ten, he accompanied his father on a 186-mile march to protest job cuts.

In 1989, the main part of the meat processing plant was named a National Historic Monument and UNESCO declared it a Historical World Heritage Site in 2015. The designated area covers 675 acres, including the factory (“kitchen to the world”), the docks on the Uruguay River, the homes of the directors, and the workers’ residential and recreation facilities, where locals and immigrants interacted and transformed Fray Bentos into a special amalgam of cosmopolitan city, town, and open-air museum that is well worth a visit.

Baron Justus von Liebig

The penetrating gaze and large nose typical of strong personalities stare from postage stamps, German banknotes, and old portraits. Justus von Liebig was born in 1803 in what is now Germany. His passion for chemistry opened the doors to the best universities of Europe, where he was a student of Gay-Lussac in Paris. Considered one of the most prominent scientists of the 19th century, von Liebig taught at the most prestigious universities and was later made a baron. His inventions and discoveries were immortalized in a dozen works that revolutionized chemistry.

Von Liebig’s achievements include the classification of foods into proteins, fats, and carbohydrates; the discovery that energy is produced by the body burning nutrients; the idea that plants can transform inorganic matter into organic; and the theory of fermentation. His most significant work led to the development of fertilizers, thereby revolutionizing agriculture and resulting in a 100% increase in wheat harvests during the five-year postwar period.

Almost all of Von Liebig’s contributions are related to human nutrition: meat extract, infant formula, and stock cubes.

Other Attractions in Fray Bentos

Solari Museum

This museum honoring internationally renowned local plastic artist Luis Alberto Solari is located on the main square. The Museum boasts an astonishingly extensive and colorful collection of paintings, etchings, and sculptures.

Young Theater

This early 20th century architectural gem opened in 1913 and was recently renovated, right down to the gilded moldings. The theater, originally constructed in an eclectic style by local landowner Miguel Young, testifies to the golden age of Fray Bentos.

Queen’s Bandstand

A gift from the Liebig Company to the town of Fray Bentos, the bandstand in the main square is an exact replica of the one where Queen Victoria listened to concerts at London’s Crystal Palace. The beautiful structure is made of wood and iron imported from Europe.

Coastal Walkway

The Walkway provides a view of the Uruguay River and the Argentinean province of Entre Ríos across the water. It also appeals to lovers of sport fishing. Visitors can eat at one of the barbecue restaurants along the river and admire the cliffs, geological formations dating back 35 million years.