Cristian Alarcón: the paradox of progress

Cristian Alarcón talks about the ups and downs of journalism, humanity’s relationship with the environment, and how Covid-19 isolation spurred him to write fiction.

By: Daniel Dominguez

Photos: Courtesy

It was time to reinvent everything, recounting events through the prism of fiction. He no longer wanted to bring back the past as a reporter. Instead, he wanted to enthusiastically tell convincing lies to create a plot that would steer through the territory of imagination to weave a story that allowed him to get carried away in the tangles of language, where the fates of his characters were not limited by the deceitful word “truth.”

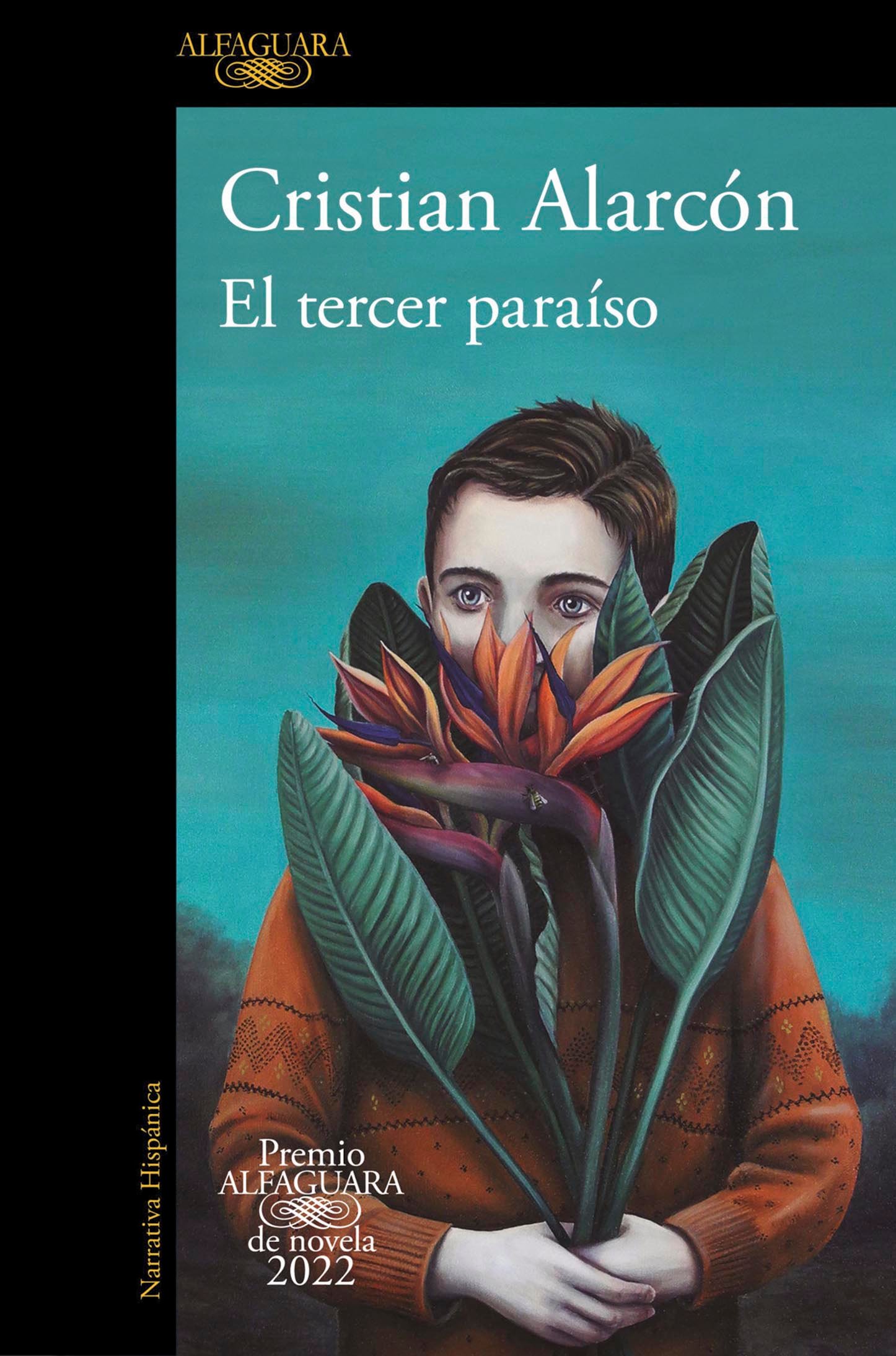

The result is El tercer paraíso (The Third Paradise), winner of the 2022 Alfaguara Novel Prize. Previous winners of this literary competition, which has been running for a quarter of a century, include other prominent writers-cum-journalists, such as Sergio Ramírez (Nicaragua), Elena Poniatowska (Mexico), Eloy Martínez (Argentina), and Laura Restrepo (Colombia).

“It’s pretty unbelievable to find myself in the company of writers who are not only sublime, but have also written great novels that are part of the overwhelming tradition of Latin American literature. At first, the news was a surprise, and then came the emotion, followed by a feeling of responsibility engendered by the significance of the Alfaguara Prize,” noted Alarcón during the Centroamérica Cuenta literary festival in Guatemala.

He believes we are at a key juncture in modern Hispano-American literature. “Everything has to do with the emergence of new alternative voices. My arrival on the sweeping shores of our literature is not so novel in the sense that I come from the universe of non-fiction, where I sought out differences, from the dissidence not only of my own sexual identity, but also of my politics and my non-fetishist approach to new theoretical and experimental frontiers in gender.”

Era hora de reinventar todo, de narrar desde la ficción. Ya no quería recuperar el pasado desde su condición de reportero. Deseaba mentir bien, con ganas, desde una trama que navegara entre lo imaginado, un argumento que le permitiera dejarse llevar por los enredos del lenguaje y que el destino de sus personajes no estuviera marcado por esa palabra engañosa que es la verdad.

El resultado es El tercer paraíso, que ganó el Premio de Novela Alfaguara de 2022, un certamen literario con 25 años de historia. En ediciones anteriores, han obtenido esta distinción importantes escritores que ejercen el periodismo, como Sergio Ramírez (Nicaragua), Elena Poniatowska (México), Eloy Martínez (Argentina) y Laura Restrepo (Colombia).

“Es algo inverosímil pertenecer a esta tradición de plumas que no solo son excelsas, sino que además han escrito grandes novelas que forman parte de una genealogía inevitable de la literatura latinoamericana. Fue una sorpresa. Luego fue una emoción y después una responsabilidad ante la contundencia del premio Alfaguara”, resaltó Alarcón, en el marco del festival literario Centroamérica Cuenta, en Guatemala.

Piensa que estamos en un momento clave de las letras hispanoamericanas contemporáneas. “Todo tiene que ver con la emergencia de nuevas voces alternativas. Mi llegada a esta playa gigantesca de nuestra literatura no es tan novedosa, en el sentido que yo ya habitaba la no ficción y lo hacía desde una búsqueda desde la diferencia, desde la disidencia no solo por mi propia identidad sexual, sino también por mi posición política, mi acercamiento no fetichista en buscar nuevas fronteras teóricas y experimentales con los géneros”.

Journalism

Authoritarian governments in Latin America are well known for restricting freedom of speech, but he feels this situation was critical in the last half of the 20th century.

“I stand in solidarity with my teacher Sergio Ramírez (self-exiled in Spain after the publication of his novel Tongolele no sabía bailar / Tongolele Didn’t Know How to Dance) who suffers one of the worst injustices: he can’t say what he thinks in his own country.”

Having said that, the current circumstances in Latin American countries do not “compare in any way with the dictatorships of the past, and those of us who suffered under them understand this viscerally since many of our colleagues died or were ‘disappeared'”

Chaos

Never before in the course of human history has it been so easy to access so much information. Knowledge is no longer the property of monarchies, clergy, or a certain political or economic class, yet human beings continue to create chaos.

This paradox of progress is evident in El tercer paraíso, in which violence is presented as a method of control perpetrated against farm workers, children, women, the environment, etc.

“That paradox is the best fountainhead of current literature. Things have improved in many ways, but we are living through a period of refraction and post-pandemic global crises. This creates uncertainty and a feeling that our economies are worsening and inequality is increasing. Despite it all, I’m an optimist.”

Alarcón advocates for honorable resistance. He proposes a philosophy based on hope that opposes the excesses of materialism and individualism, without falling into propaganda, banality, or self-help rhetoric.

Pandemic

During the first year of the pandemic, he isolated in a 1902 wood and iron cabin in Chile’s Patagonia region to finish a story he had first drafted two years before.

“I don’t think I would have been able to write it anywhere but in Chile. It was a return to my roots. I could have stayed in the outskirts of Buenos Aires,” but something unknowable drew him back to his country. “I had the lake, the weather, the firewood, the silent nights, the mornings with birdsong, thinking about what I would eat that day, knowing that I would finish such and such a chapter that day, resisting the temptation to grab a launch that would take me over to my cousins, who used to cook lamb for me.”

Solitudes

His main character is a frugal, single, gay 50-year-old father (not himself, he points out) who was alone when Covid-19 arrived, forcing him into solitary isolation like so many others. To keep himself busy, he builds a garden on a small farm in Buenos Aires, which leads to a close relationship with the rain, the sun, the vegetables, the flowers…in short, all those other beings that share our space.

The story explores a novelist’s solitude, a solitude without distractions, a solitude of a character who decides to be alone, a solitude imposed by Covid-19.

It is a rediscovery of solitude. “Solitude gets a bad rap; we need to get over that. We need to stop thinking that we need to take up with another person be happy, like in those Mexican, Colombian, and Argentinean soap operas. This obsession with togetherness has held many of us captive to shared unhappiness instead of allowing us the happiness of solitude.”

Dictatorships

Influenced by Juan Rulfo, William Faulkner, José Donoso, and Gabriel García Márquez, El tercer paraíso (dedicated to Pablo, his adopted 13-year-old son), is a novel about exile, the dictatorships of the Southern Cone, and the arbitrariness of memory.

“Nowadays, there are many young activists committed to changing their world. That is something we haven’t seen since the struggles in the 1970s to restore our democracies.”

Leave a Reply