Fog

By María Pérez-Talavera

Illustrated by Henry González

Selection and Compilation Carolina Fonseca

We know that every morning before dawn he descends the gravel path to the terrace, clasping a clay cup and augmenting the fog with his vaporous exhalations. The wet earth seeps into the black coffee, infusing it with a taste of greenery. The narrow pier doesn’t creak under his footsteps; his weight is as immaterial as the idea of covering up to hunker on the edge until the sun rises.

The lake is immersed in its waters, wet with cold and blanketed in algae. Foamy skirts hug the shore and gulp air among the liquid burbling that the old man takes in quietly, as if it were telling him something only he can hear. Glimmers still concealed behind the volcanoes burnish the body of water and the entire mass trembles when birds split its skin with their fragile wings and tiny beaks. Slim rays begin to unveil the other shore but the fog insists on smudging it with its icy breath. The buzzard croaks, hoots, and whistles while the old man stamps directional movement onto the space: he rambles from one side to the other, parting the same air also cleaved by a dragonfly and a shooting star; he tosses pebbles weighted with memories at the beach. At least that’s what it seems like to me.

We remember the day he descended from the summit. He arrived in town in December, around the time of Christmas Eve midnight mass, with a cart full of pine and a bag stuffed with pine cones that he flung into the center of the plaza one by one. We boys pounced on the loot, filling our pockets and forming sacks with our ponchos. We turned the pine cones into grenades, balls, and amulets; they fueled the fires in our homes and even decorated Christmas. I approached to thank him, but the cloudiness of his eyes, hidden behind a frosted layer, stopped me in my tracks. I didn’t know if he was looking at me and I didn’t want to find out. He raised his arm and indicated a point behind me. I turned slowly —the hairs on the back of my neck standing on end— looking in the direction of his crooked finger until I spotted my mother, buoyantly gesticulating and calling me. I never heard his voice.

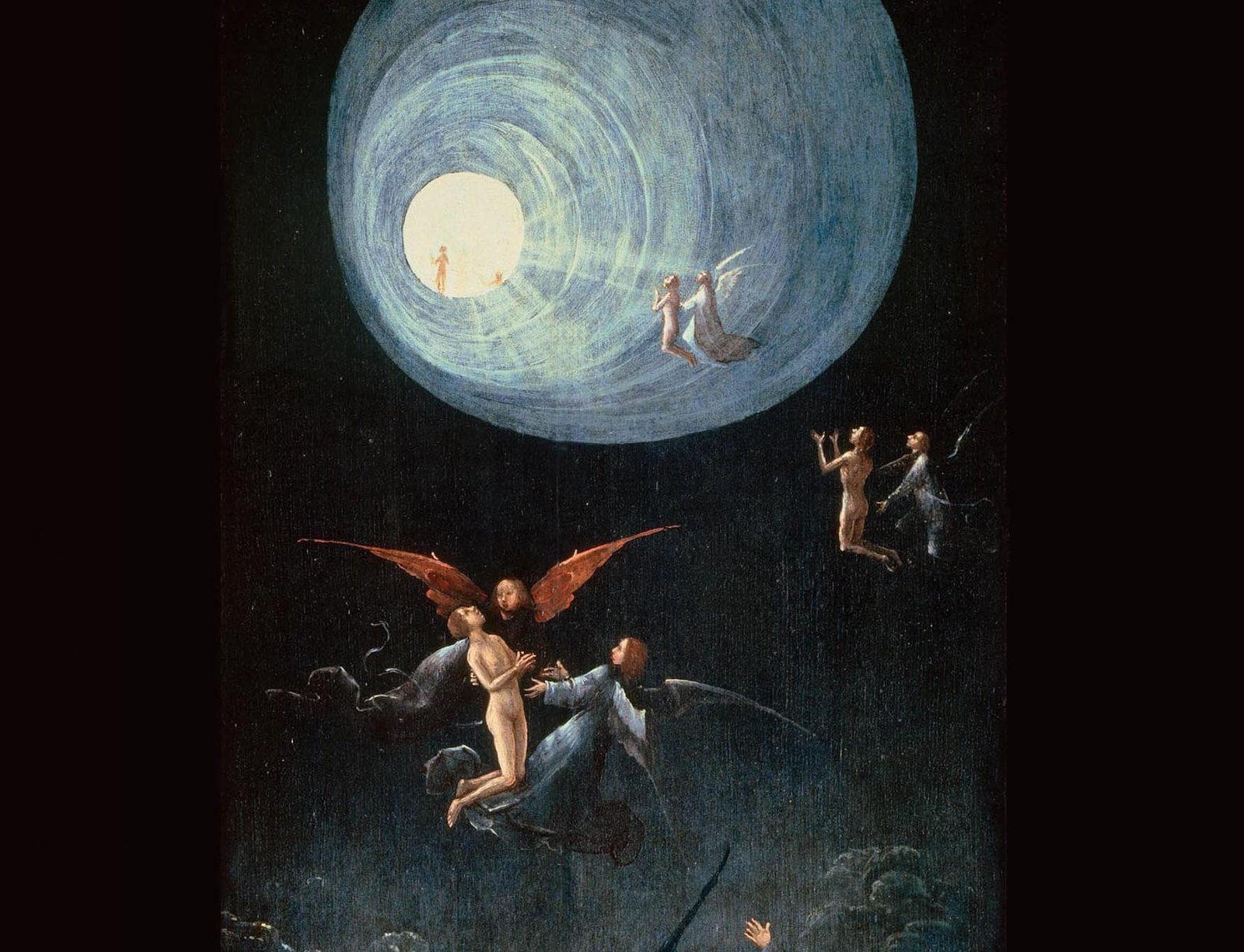

The air grows heavy, and a mist rises off the mirror of the cove that swallows his milky gaze. The splashing of his sunken eyes is audible from the footpath. His sighs mingle with the fog —the all-pervasive fog— and in the distance we see him babble mute words that climb the mountain to melt in the lava that saturates it, after which it mutates into the scent of sage that permeates us and fades, since not even an echo survives in this opaque distance.

We assume that the old man tells the solitude what we would have liked to understand. An inaudible whisper encrypts the color of his craggy skin, the scars that mark his body, the blood of indigenous warriors via an indigenous woman through a white man with stale sweat and yellow teeth that runs through his swollen veins, the pain of those absences that follow him wherever he goes, the mystery that fogs his eyes. Perhaps his mutterings speak to the lake of his origins in the hope that its nearly marine current will take him back there. Perhaps he confesses to a boat his fear of jumping into its belly and being dragged to the other side to reunite with whatever he left.

There, with whomever is waiting for him, sit this old man with a banal life we don’t know, whom we observe from a distance, without noticing the subtle patterns of his existence, how he always descends with the fog and leaves when it dissipates, how the fog, his steaming cup, and he himself mingle in each breath, a mist that clouds his vision. We don’t see how the cold doesn’t penetrate his skin, how his flickering shadow is the natural poetry of any hamlet on the lakeshore, where an entire ecstatic town is embraced by the butterfly-light impression of his arrival, his presence and absence, the fibers that he plays like a melodious harp when he bursts into time and space of a hoary era that seems to have given birth to the pleasure of losing ourselves in the peace of an ancestral landscape.

The birds belabor their song, they reiterate trills that bounce off who knows where. In the blink of an eye, the light pinkens the two slopes that rise into a V, and saturates the waters on its journey through the apex. On the other side, firefly-light bulbs ignite the verge of the lake. The fishers are already fording the depths and flats, shooing away the mantle that covers their sustenance: the hope of the day dangles on the point of a hook. At dawn, when the morning is clean-scrubbed, the old man has already withdrawn to his pine cabin in the heights. The only window sports a curtain of pine cones that protects him from the light and hides him from our sight; a curtain that dances with the wind at dusk, weaves a beautiful play of light on the wood porch, and lets in the fog at night.